人体肠道是目前已知微生物群密度最大的微生态环境,该环境中人体细胞、细菌、古细菌、原生动物、真菌及不具有细胞结构的病毒(如噬菌体)以动态平衡状态共存,它们彼此之间的相互作用对人体健康有着十分重要的影响,其中细菌及噬菌体是人体微生态中最为丰富的组分[1]。目前肠道微生物群的稳态失衡已被证明与多种疾病有关,相关研究主要着力于探究稳态失衡发生过程及如何恢复其平衡状态[2]。

大量的宏基因组数据表明,噬菌体是人体微生态系统中最多样化却仍未被准确识别的成分[3]。了解肠道微生物群中噬菌体群落的结构与功能对于我们更系统地了解人体微生物组,并应用于人体健康相关的研究或产业均至关重要。近年来,人体噬菌体组尤其是肠道噬菌体组正在成为微生态学研究中新的热点。

人体噬菌体组是指不同生态位噬菌体群的基因组及整合在宿主菌基因中噬菌体遗传元件(原噬菌体)的总和。目前,噬菌体组的相关研究除涉及其与人体健康或疾病状态关系外,还包括不同人群体内肠道噬菌体组成结构和丰度的差异、噬菌体在微生物群落演化过程中发挥的作用和相关机制等。

1 人体肠道噬菌体组的组成特征及其对人体健康的影响研究人员通过观察和分析发现人体粪便样品中分离的病毒颗粒主要以噬菌体为主[2]。目前已知的肠道噬菌体组主要由DNA噬菌体组成,其中大多数属于有尾噬菌体目(Caudovirales)和微小噬菌体科(Microviridae)[4-5]。此外,家庭成员等共享生活空间的个体倾向于有更为相似的肠道噬菌体群[6-7]。Norman等在来自不同地域的健康个体中鉴定出23个“核心噬菌体”(>50%的个体共有)和155个“常见噬菌体”(20%~50%的个体共有),并由此提出健康肠道噬菌体(healthy gut phageome, HGP)的概念[8]。当前研究发现的在全球分布最广泛的肠道噬菌体是一种可感染拟杆菌目细菌的新型噬菌体,称为crAss样噬菌体(crAss-like bacteriophages)[9]。健康个体中存在的这些共有噬菌体引发人们对其在维持人体健康方面所起作用的思考。同时,肠道噬菌体组也存在一定程度的个体特异性,研究发现几乎每个个体的肠道噬菌体组中有超过50%的噬菌体成员是相对独特的,并且噬菌体类型多样性和出现频率呈现高度的个体差异[3, 10]。

肠道中的常驻噬菌体组对人体健康有着诸多积极影响,甚至可以帮助人体抵御病原体的侵袭。前噬菌体是噬菌体在健康人肠道中存在的主要形式,为其宿主提供生存优势且改变噬菌体-细菌动力学[11-14],通过自身在宿主之间的水平转移进行有益基因的传播,赋予人体抵抗外来病原体的能力[15-16]。Barr等提出了一种与肠道裂解性噬菌体相关的防御致病菌模型:噬菌体颗粒黏附于黏膜并减少自身扩散运动,以赋予人类上皮组织防御病原体感染的能力[17]。研究还发现噬菌体直接导致其宿主菌丰度变化,通过细菌间相互作用引起级联效应,进而使其他肠道细菌丰度随之发生改变;并且能通过引起微生物群变化而间接地对肠道代谢产生影响[18]。另外,有研究发现烈性的大肠埃希菌T4噬菌体还可以发挥免疫抑制作用,参与肠道免疫细胞的下调和炎症反应的控制[19]。对于健康或疾病等不同机体状态下的肠道噬菌体组进行分析,有助于加深我们对健康状态下肠道噬菌体组的认识,并为从疾病状态中恢复人体微生物群平衡提供思路。

2 人体肠道噬菌体组年龄依赖性的演替已有研究表明在生命最初的2~3年内,健康的新生儿体内从近乎无菌的状态发展为具有成熟稳定的多样性微生物群的状态;并且人体微生物群可随着机体年龄增长所产生的一系列内环境变化而逐渐形成老年期的结构特征[20-21]。Breitbart等对1周~3个月内婴儿的肠道噬菌体进行了研究,结果显示新生儿的肠道噬菌体多样性极低却有着较高的活性[22]。另外两项研究分别检测了人类个体生命最初2年和2.5年内的微生物群的动态变化,结果表明婴儿出生后(1~4 d)肠道迅速被噬菌体定植,且相比于成年个体,婴儿间的肠道噬菌体组更为相似[23-24]。Lim等发现人体肠道噬菌体的丰度在生命最初1~4 d最高,而后可能是这种噬菌体群的高度多样性不受环境内低丰度微生物等的支持,导致噬菌体捕食压力的产生和多样性的下降,这也表明微生物群成员丰度的增加和微生物群组成的变化推动了噬菌体群的转变[23]。在人体发育过程中,肠道内有尾噬菌体目(Caudovirales)成员多样性的减少,并伴随着微小噬菌体科(Microviridae)噬菌体多样性和丰度的增加,以及整体微生物群组成的变化[2]。婴儿肠道微生物群的成熟以病毒组分丰度和多样性的降低以及细菌组分丰度和多样性的增加为特征[25]。但对于生命初期肠道噬菌体的高丰度和低多样性的特征仍没有研究可给出合理解释[3]。

肠道噬菌体组的结构随着年龄而呈现不同的群落特征[26]。但我们对于噬菌体组在微生物群从成熟期到老年期演化过程中的作用和变化情况知之甚少[3]。

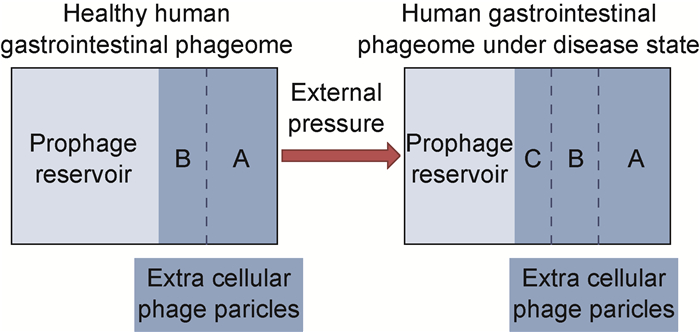

3 人体肠道内噬菌体组与某些疾病存在关联在健康人体肠道内,正常情况下应只有一小部分前噬菌体被诱导激活,成为独立的胞外噬菌体,已有科学家提出肠道中前噬菌体诱导活化的比率增加或者裂解性噬菌体的占比增加将导致噬菌体群失调,且这种失调与许多疾病相关[2-3](见图 1)。有研究人员提出以群落改组模型来解释前噬菌体诱导活化率增加导致人体转向疾病状态的过程,即假定前噬菌体的诱导活化比例增加后降低共生菌与致病菌的比例,从而引起肠道微生物群组成的变化[27]。

|

| The light blue part represents the prophage reservoir of the human intestinal tract, and the dark blue part represents the extracellular phage particles. A: Lytic phage. B: Extracellular phage produced by prophage-induced activation in a healthy state. C: Increased extracellular phage produced by prophage-induced activation under disease conditions. 图 1 健康或疾病状态下的人体肠道噬菌体组 Fig. 1 Human intestinal phageome in healthy or disease states |

研究表明,肠道内前噬菌体的激活诱导与周围环境压力有关,比如饮食、抗生素、疾病相关炎症等[2, 28]。此外,疾病状态也会影响肠道噬菌体组。比如克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease,CD)、溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)等肠道疾病患者体内肠道噬菌体组与健康人之间存在明显差别[8, 29-32]。另外,研究人员发现白血病、糖尿病及一些涉及呼吸和循环系统的非肠道疾病患者体内也存在肠道噬菌体群的改变[8, 29, 33-36],见表 1。近年来,许多研究结果突出了肠道噬菌体组作为健康或疾病状态的生物标志物的潜力[37]。然而,目前相关研究仅停留在基于种群丰度的关系和变化趋势上,驱动变化产生的机制仍然未知。

| Disease | Intestinal phageome alterations |

| Crohn’s disease | The number of extracellular phages increases and their diversity is low, and the differences between different individuals are large [8, 29-31, 33]. |

| Ulcerative colitis | Amplification of Caudovirales phages, but mucosal Caudovirales diversity, enrichment and uniformity decrease. Escherichia phage and Enterobacteria phage are more abundant in the mucosa. A variety of viruses, such as phages associated with host bacterial adaptability and pathogenicity, are significantly enriched in the mucosa [32]. |

| Some internal (respiratory and circulatory diseases) diseases and leukemia | Some patients’ feces contain a significant high number of toxic phages belonging to multiple serotypes. Samples collected from patients often contain more coliphages [35]. |

| Type Ⅰ diabetes | Phageome diversity and richness are low; There was no difference in the relative abundance of the phageome, but the number of phages varied greatly. The difference between cases and controls increased with age [34]. |

| Type Ⅱ diabetes | Intestinal Myoviridae, Podoviridae, Siphoviridae increased significantly, including 7 core pOTUs, the host bacteria are presumed to be Enterobacter, Escherichia, Lactobacillus, Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus [36]. |

健康人体内的微生物群具备受干扰后建立新型稳态的能力,研究表明肠道噬菌体组可能在此过程中起到促进作用[37]。粪便微生物移植(fecal microbiota transplantation,FMT)是一种靶向人体内微生物群的治疗方法,有研究人员跟踪研究了在FMT治疗期间噬菌体组在稳态恢复过程中的作用,发现有一些噬菌体成功地从供体转移到患者体内并发挥积极作用[38]。Ott等的研究表明,仅肠道噬菌体组本身可能足以治愈艰难梭菌感染(clostridium difficile infection,CDI)并促进健康微生物组结构的恢复[39]。以上研究均证明了肠道噬菌体组具有恢复健康微生物组和重建愈后肠道平衡的重要作用。

综上所述,目前的研究结果支持健康人和患者之间肠道噬菌体组的丰度和多样性存在显著差异的观点,肠道噬菌体组为揭示不同疾病的机制、开发健康和疾病标记物以及开展更有效的诊断和治疗方法提供了新思路[3]。但仍无法判断肠道中噬菌体群体的改变是疾病产生的结果还是疾病的诱因。肠道噬菌体组与健康和疾病之间的复杂关系仍需我们进一步探索。

5 结语目前的研究充分体现了肠道噬菌体组与人体健康或疾病状态的密切关系及在维持或恢复肠道健康稳态过程中的重要作用。健康人肠道中的噬菌体主要以前噬菌体形式存在,且影响人体健康。但是,肠道噬菌体组相关领域中还有许多问题仍未解决。比如:肠道不同部位噬菌体群的差异和差异产生的原因,以及它们的细菌宿主谱;健康人体内裂解性噬菌体的来源;肠道内噬菌体以前噬菌体为主要形式的成因。

健康人体肠道内噬菌体群由核心噬菌体、常见噬菌体和独特性噬菌体三类组成,科学家以此为基础提出HGP概念。目前,有研究证明肠道噬菌体组本身便足以治愈疾病并促进健康微生物组的稳态恢复,但是,仍未有研究结果表明不同人种,不同地区人群的噬菌体组是否存在差异及差异程度。此外,对于肠道噬菌体组在微生物群从成熟期到老年期演化过程中的变化和发挥的作用还未研究清楚。

相关研究技术的发展决定着肠道噬菌体组的研究进展,现已经有一系列较为成熟的研究手段。但是目前在肠道噬菌体分类方面的技术还有待改进[40]。此外,宏基因组学对于噬菌体组研究有着革命性的推动作用,相信随着宏基因组技术的不断完善,对噬菌体组的认识也会逐渐深入。

关于肠道噬菌体与宿主菌的互作动力学研究,未来应着眼于相关数学模型的开发以及特定细菌定植的无菌小鼠模型或离体肠道模型的应用[41]。此外,也可以利用肠道噬菌体组对微生物组的影响来开发新型研究手段。如基于噬菌体与其宿主菌的互作关系,我们可利用噬菌体特异性去除研究对象体内的某些细菌并观察其表型,为更好地研究人体微生物群中特定细菌或几种细菌组合对人体健康的影响提供合适的模型。

目前,肠道噬菌体组的研究还处于初步阶段。相信随着分析技术的不断进步,对肠道噬菌体组与人体健康的关系将有更深的了解,并会以此为基础开发出更有效、更精准的治疗方法。

| [1] |

Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome[J]. Genome Med, 2016, 8(1): 51.

[DOI]

|

| [2] |

Manrique P, Dills M, Young MJ. The human gut phage community and its implications for health and disease[J]. Viruses, 2017, 9(6): E141.

[DOI]

|

| [3] |

Bakhshinejad B, Ghiasvand S. Bacteriophages in the human gut: our fellow travelers throughout life and potential biomarkers of heath or disease[J]. Virus Res, 2017, 240: 47-55.

[DOI]

|

| [4] |

Krishnamurthy SR, Janowski AB, Zhao G, Barouch D, Wang D. Hyperexpansion of RNA bacteriophage diversity[J]. PLoS Biol, 2016, 14(3): e1002409.

[DOI]

|

| [5] |

Minot S, Sinha R, Chen J, Li H, Keilbaugh SA, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Bushman FD. The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet[J]. Genome Res, 2011, 21(10): 1616-1625.

[DOI]

|

| [6] |

Robles-Sikisaka R, Ly M, Boehm T, Naidu M, Salzman J, Pride DT. Association between living environment and human oral viral ecology[J]. ISME J, 2013, 7(9): 1710-1724.

[DOI]

|

| [7] |

Ly M, Jones MB, Abeles SR, Santiago-Rodriguez TM, Gao J, Chan IC, Ghose C, Pride DT. Transmission of viruses via our microbiomes[J]. Microbiome, 2016, 4(1): 64.

[DOI]

|

| [8] |

Norman JM, Handley SA, Baldridge MT, Droit L, Liu CY, Keller BC, Kambal A, Monaco CL, Zhao G, Fleshner P, Stappenbeck TS, McGovern DP, Keshavarzian A, Mutlu EA, Sauk J, Gevers D, Xavier RJ, Wang D, Parkes M, Virgin HW. Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Cell, 2015, 160(3): 447-460.

[DOI]

|

| [9] |

Dutilh BE, Cassman N, McNair K, Sanchez SE, Silva GG, Boling L, Barr JJ, Speth DR, Seguritan V, Aziz RK, Felts B, Dinsdale EA, Mokili JL, Edwards RA. A highly abundant bacteriophage discovered in the unknown sequences of human faecal metagenomes[J]. Nat Commun, 2014, 5: 4498.

[DOI]

|

| [10] |

Reyes A, Haynes M, Hanson N, Angly FE, Heath AC, Rohwer F, Gordon JI. Viruses in the faecal microbiota of monozygotic twins and their mothers[J]. Nature, 2010, 466(7304): 334-338.

[DOI]

|

| [11] |

Reyes A, Semenkovich NP, Whiteson K, Rohwer F, Gordon JI. Going viral: next-generation sequencing applied to phage populations in the human gut[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2012, 10(9): 607-617.

[DOI]

|

| [12] |

Wang X, Kim Y, Ma Q, Hong SH, Pokusaeva K, Sturino JM, Wood TK. Cryptic prophages help bacteria cope with adverse environments[J]. Nat Commun, 2010, 1: 147.

[DOI]

|

| [13] |

Stern A, Mick E, Tirosh I, Sagy O, Sorek R. CRISPR targeting reveals a reservoir of common phages associated with the human gut microbiome[J]. Genome Res, 2012, 22(10): 1985-1994.

[DOI]

|

| [14] |

Silveira CB, Rohwer FL. Piggyback-the-Winner in host-associated microbial communities[J]. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes, 2016, 2: 16010.

[DOI]

|

| [15] |

Boyd JS. Immunity of lysogenic bacteria[J]. Nature, 1956, 178(4525): 141.

[DOI]

|

| [16] |

Williams HT. Phage-induced diversification improves host evolvability[J]. BMC Evol Biol, 2013, 13: 17.

[DOI]

|

| [17] |

Barr JJ, Auro R, Furlan M, Whiteson KL, Erb ML, Pogliano J, Stotland A, Wolkowicz R, Cutting AS, Doran KS, Salamon P, Youle M, Rohwer F. Bacteriophage adhering to mucus provide a non-host-derived immunity[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2013, 110(26): 10771-10776.

[DOI]

|

| [18] |

Hsu BB, Gibson TE, Yeliseyev V, Liu Q, Lyon L, Bry L, Silver PA, Gerber GK. Dynamic modulation of the gut microbiota and metabolome by bacteriophages in a mouse model[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2019, 25(6): 803-814.

[DOI]

|

| [19] |

Górski A, Miȩdzybrodzki R, Borysowski J, Dąbrowska K, Wierzbicki P, Ohams M, Korczak-Kowalska G, Olszowska-Zaremba N, Łusiak-Szelachowska M, Kłak M, Jończyk E, Kaniuga E, Gołaś A, Purchla S, Weber-Dąbrowska B, Letkiewicz S, Fortuna W, Szufnarowski K, Pawełczyk Z, Rogó P, Kłosowska D. Phage as a modulator of immune responses: practical implications for phage therapy[J]. Adv Virus Res, 2012, 83: 41-71.

[DOI]

|

| [20] |

Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon J I. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography[J]. Nature, 2012, 486(7402): 222-227.

[DOI]

|

| [21] |

O'Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota and aging[J]. Science, 2015, 350(6265): 1214-1215.

[DOI]

|

| [22] |

Breitbart M, Haynes M, Kelley S, Angly F, Edwards RA, Felts B, Mahaffy JM, Mueller J, Nulton J, Rayhawk S, Rodriguez-Brito B, Salamon P, Rohwer F. Viral diversity and dynamics in an infant gut[J]. Res Microbiol, 2008, 159(5): 367-373.

[DOI]

|

| [23] |

Lim ES, Zhou Y, Zhao G, Bauer IK, Droit L, Ndao IM, Warner BB, Tarr PI, Wang D, Holtz LR. Early life dynamics of the human gut virome and bacterial microbiome in infants[J]. Nat Med, 2015, 21(10): 1228-1234.

[DOI]

|

| [24] |

Reyes A, Blanton LV, Cao S, Zhao G, Manary M, Trehan I, Smith MI, Wang D, Virgin HW, Rohwer F, Gordon JI. Gut DNA viromes of Malawian twins discordant for severe acute malnutrition[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(38): 11941-11946.

[DOI]

|

| [25] |

Shkoporov AN, Hill C. Bacteriophages of the human gut: the "known unknown" of the microbiome[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2019, 25(2): 195-209.

[DOI]

|

| [26] |

Dalmasso M, Hill C, Ross RP. Exploiting gut bacteriophages for human health[J]. Trends Microbiol, 2014, 22(7): 399-405.

[DOI]

|

| [27] |

Licznerska K, Nejman-Falenczyk B, Bloch S, Dydecka A, Topka G, Gasior T, Wegrzyn A, Wegrzyn G. Oxidative stress in shiga toxin production by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli[J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2016, 2016: 3578368.

[DOI]

|

| [28] |

Oh JH, Alexander LM, Pan M, Schueler KL, Keller MP, Attie AD, Walter J, van Pijkeren JP. Dietary fructose and microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote bacteriophage production in the gut symbiont Lactobacillus reuteri[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2019, 25(2): 273-284.

[DOI]

|

| [29] |

Lepage P, Colombet J, Marteau P, Sime-Ngando T, Doré J, Leclerc M. Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease: a role for bacteriophages?[J]. Gut, 2008, 57(3): 424-425.

[DOI]

|

| [30] |

Wagner J, Maksimovic J, Farries G, Sim WH, Bishop RF, Cameron DJ, Catto-Smith AG, Kirkwood CD. Bacteriophages in gut samples from pediatric Crohn's disease patients: metagenomic analysis using 454 pyrosequencing[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19(8): 1598-1608.

[DOI]

|

| [31] |

Pérez-Brocal V, García-López R, Vázquez-Castellanos JF, Nos P, Beltrán B, Latorre A, Moya A. Study of the viral and microbial communities associated with Crohn's disease: a metagenomic approach[J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2013, 4: e36.

[DOI]

|

| [32] |

Zuo T, Lu XJ, Zhang Y, Cheung CP, Lam S, Zhang F, Tang W, Ching JYL, Zhao R, Chan PKS, Sung JJY, Yu J, Chan FKL, Cao Q, Sheng JQ, Ng SC. Gut mucosal virome alterations in ulcerative colitis[J]. Gut, 2019, 68(7): 1169-1179.

[DOI]

|

| [33] |

Manrique P, Bolduc B, Walk ST, van der Oost J, de Vos WM, Young MJ. Healthy human gut phageome[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2016, 113(37): 10400-10405.

[DOI]

|

| [34] |

Zhao G, Vatanen T, Droit L, Park A, Kostic AD, Poon TW, Vlamakis H, Siljander H, Härkönen T, Hämäläinen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Ilonen J, Wang D, Knip M, Xavier RJ, Virgin HW. Intestinal virome changes precede autoimmunity in type Ⅰ diabetes-susceptible children[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2017, 114(30): E6166-E6175.

[DOI]

|

| [35] |

Furuse K, Osawa S, Kawashiro J, Tanaka R, Ozawa A, Sawamura S, Yanagawa Y, Nagao T, Watanabe I. Bacteriophage distribution in human faeces: continuous survey of healthy subjects and patients with internal and leukaemic diseases[J]. J Gen Virol, 1983, 64(Pt 9): 2039-2043.

[DOI]

|

| [36] |

Ma Y, You X, Mai G, Tokuyasu T, Liu C. A human gut phage catalog correlates the gut phageome with type 2 diabetes[J]. Microbiome, 2018, 6(1): 24.

[DOI]

|

| [37] |

李婷华, 郭晓奎. 肠道噬菌体作为健康与疾病的标志物的研究进展[J]. 中国微生态学杂志, 2015, 27(10): 1238-1241. [URI]

|

| [38] |

Broecker F, Klumpp J, Schuppler M, Russo G, Biedermann L, Hombach M, Rogler G, Moelling K. Long-term changes of bacterial and viral compositions in the intestine of a recovered Clostridium difficile patient after fecal microbiota transplantation[J]. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud, 2016, 2(1): a000448.

[DOI]

|

| [39] |

Ott SJ, Waetzig GH, Rehman A, Moltzau-Anderson J, Bharti R, Grasis JA, Cassidy L, Tholey A, Fickenscher H, Seegert D, Rosenstiel P, Schreiber S. Efficacy of sterile fecal filtrate transfer for treating patients with Clostridium difficile infection[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152(4): 799-811, 811e1-811e7.

[DOI]

|

| [40] |

Ogilvie LA, Jones BV. The human gut virome: a multifaceted majority[J]. Front Microbiol, 2015, 6: 918.

[DOI]

|

| [41] |

Reyes A, Wu M, McNulty NP, Rohwer FL, Gordon J I. Gnotobiotic mouse model of phage-bacterial host dynamics in the human gut[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2013, 110(50): 20236-20241.

[DOI]

|

2019, Vol. 14

2019, Vol. 14