肿瘤通过多种机制来逃避机体免疫系统的监视和攻击,包括改变肿瘤相关抗原表达和表面分子结构、诱导免疫抑制细胞和分泌抑制性细胞因子、建立免疫抑制的肿瘤微环境等,其中免疫检查点通路在肿瘤免疫逃逸中发挥了重要作用[1]。2018年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖授予美国的Allison教授和日本的Honjo教授[2],以表彰他们在细胞毒性T淋巴细胞抗原4(cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4, CTLA-4)和程序性死亡受体1(programmed death receptor 1, PD-1)相关领域研究与应用中所作的杰出贡献。目前,已批准了几种针对免疫检查点通路的抑制剂用于多种肿瘤的治疗,并取得成功[3-5],这是近年来抗肿瘤免疫治疗领域的重要进展。然而,这类新型抗肿瘤药物广泛应用带来相应的毒副作用不容忽视,尤其是随之而来的机会性感染更加值得重视。本文拟针对免疫检查点抑制剂(immune checkpoint inhibitors, ICI)的应用及其所致的感染并发症方面进行综述,以期为相应的防治提供新的认识。

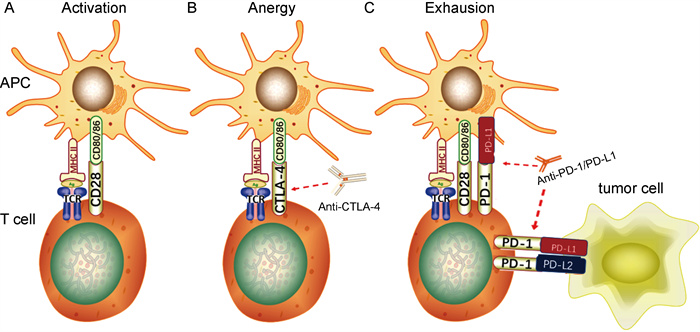

1 T细胞活化和免疫检查点受体T细胞表面分布识别抗原的T细胞抗原受体(T cell antigen receptor, TCR)和调控活化的共刺激受体,其活化依赖双信号:由抗原提呈细胞(antigen-presenting cells, APC)提呈的抗原肽-主要组织相容性复合体(major histocompatibility complex, MHC)提供给TCR的信号,称为第一信号;APC表面的共刺激分子与T细胞表面相应受体结合后提供给T细胞使之完全活化的信号,称为第二信号[4](见图 1A)。常见的共刺激分子有CD80和CD86,相应共刺激受体有两类:①持续表达于T细胞表面并提供T细胞活化第二信号的受体(如CD28);②主要表达于活化T细胞表面并发挥负向免疫调控作用的受体,即免疫检查点受体(immune checkpoint receptors, ICR),包括CTLA-4、PD-1、B和T淋巴细胞衰减蛋白(B and T lymphocyte attenuator, BTLA)、淋巴细胞激活基因3(lymphocyte activation gene 3, LAG3)、T细胞免疫球蛋白和黏蛋白3(T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-3, TIM-3)、腺苷A2a受体(adenosine A2a receptor, A2aR)等[6],分别与各自的配体结合而抑制T细胞功能。

|

| A. T细胞活化依赖双信号:由APC提呈的抗原肽-MHC复合物与T细胞表面TCR结合提供第一信号,APC表面的共刺激分子(如CD80/86)与T细胞表面相应受体(如CD28)结合后提供第二信号; B. CTLA-4通过与CD28竞争性结合CD80/86来抑制T细胞活化的第二信号,使之进入失能状态;抗CTLA-4抗体阻断CTLA-4与CD80/86结合,从而解除对T细胞活化的抑制; C. T细胞表面的PD-1通过与APC、肿瘤细胞表面PD-L1/2结合,抑制TCR信号通路上的关键分子,从而抑制T细胞功能,使其进入衰竭状态;抗PD-1/PD-L1抗体阻断PD-1/PD-L1的相互作用,使T细胞恢复功能。 图 1 CTLA-4、PD-1/PD-L1的作用机制 Fig. 1 Mechanisms of CTLA-4、PD-1/PD-L1 |

ICR可与配体在T细胞激活和作用的不同阶段进行结合而发挥对T细胞功能的负向调控作用,如CTLA-4、LAG3、TIM-3在T细胞启动阶段限制T细胞激活[6];而PD-1在T细胞效应阶段发挥负向调节作用[7]。正常情况下,接受信号的T细胞在活化的同时上调其表面的ICR,触发抑制T细胞功能的信号通路,使T细胞衰竭,以维持自身免疫耐受、调节免疫平衡[7-8]。肿瘤细胞正是通过上调ICR而抑制T细胞功能,实现免疫逃避;而使用ICI阻断ICR与配体结合,则能减少因ICR上调而对效应T细胞产生的抑制作用,从而改善肿瘤特异性免疫反应,达到有效治疗的作用。以下主要针对PD-1及其配体[程序性死亡配体1(programmed death ligand 1, PD-L1)]以及CTLA-4的ICI进行介绍。

1.1 CTLA-4CTLA-4(即CD152)是T细胞表面重要的ICR,属于CD28免疫球蛋白超家族,主要表达于活化的CD4+和CD8+T细胞表面。CTLA-4的配体为APC表面的CD80和CD86,主要在淋巴组织中发挥免疫抑制作用。

CTLA-4的作用机制如下:①接受活化信号的T细胞过度表达CTLA-4,通过竞争性结合CD80/CD86来抑制CD28的作用,同时经反式内吞而减少CD80/CD86表达,抑制APC传递给T细胞并使之激活的第二信号[9];②CTLA-4结合了配体,其胞内段免疫受体酪氨酸抑制基序(immune-receptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif, ITIM)中酪氨酸残基被磷酸化而进一步募集酪氨酸磷酸酶(SHP-1),从而使T细胞活化途径中的多个重要信号分子去磷酸化,最终抑制T细胞活化[10];③调节性T细胞(regulatory T cell, Treg细胞)持续性表达CTLA-4,下调APC表面CD80/CD86水平而抑制CD28共刺激信号通路,最终抑制效应T细胞功能[6]。

针对CTLA-4的单克隆抗体通过阻断CTLA-4与CD80/CD86结合,解除其对T细胞的抑制,从而发挥抗肿瘤作用(见图 1B)。

1.2 PD-1PD-1(即CD279)是免疫细胞表面另一个重要的ICR,也属于CD28免疫球蛋白超家族,主要表达于活化的CD4+和CD8+T细胞上,也可表达在B细胞、单核细胞、自然杀伤细胞、树突状细胞等细胞表面[7]。PD-1有PD-L1和PD-L2两种配体,PD-L1广泛表达于肿瘤细胞和肿瘤微环境中各种细胞表面,其表达量与许多类型肿瘤(如非小细胞肺癌[11]和黑色素瘤[12])的预后密切相关;而PD-L2的分布较局限,主要在巨噬细胞、树突状细胞和某些B细胞亚类的表面表达,在某些B细胞淋巴瘤(如原发性纵隔B细胞淋巴瘤、滤泡B细胞淋巴瘤和霍奇金病)的B细胞上高度上调[13]。

PD-1与配体结合后可通过免疫受体酪氨酸转换基序(immune-receptor tyrosine-based switch motif, ITSM)来募集含SH2结构域的酪氨酸蛋白磷酸酶[rc homology2(SH2)domain-containg protein tyrosine phosphatase(PTPase), SHP-2],使TCR/CD28信号通路上多个关键分子去磷酸化,抑制T细胞增殖[14]、诱导T细胞耐受和凋亡[15],使肿瘤微环境中T细胞效应功能降低,从而介导肿瘤免疫逃逸。高表达PD-1和PD-L1的Foxp3+ Treg细胞通过抑制Akt/mTOR信号通路使初始CD4+T细胞分化为Treg细胞,并通过上调Foxp3来诱导和维持Treg细胞,从而抑制效应T细胞功能[16]。

针对PD-1和PD-L1的单克隆抗体阻断了PD-1/PD-L1相互作用,解除其对T细胞的抑制作用,从而恢复抗肿瘤功能(见图 1C)。针对PD-L2的抗体目前还未用于临床。

2 ICI的种类及适应证目前有以下几种ICI被批准用于治疗各种肿瘤。

Ipilimumab[17]是针对CTLA-4的全人源化IgG1单抗,在2011年被批准用于晚期黑色素瘤,开创了ICI在肿瘤免疫治疗中的先河,并在临床应用中取得令人瞩目的效果[18],是第1种被证实可以延长晚期黑色素瘤患者生存期的药物。

Pembrolizumab[19]和Nivolumab[20]是针对PD-1的IgG4,2014年被批准用于治疗晚期黑色素瘤,随后不断扩大适应证到许多实体瘤(如肺癌、胃癌、结肠癌、尿路上皮癌、宫颈癌等)以及血液系统肿瘤(如霍奇金淋巴瘤)。2015年Nivolumab被批准用于治疗非小细胞肺癌(non-small cell lung cancer, NSCLC)后,因其疗效显著已成为治疗转移性NSCLC的一线药物。另外,Nivolumab与Ipilimumab的联合使用已被批准用于治疗晚期黑色素瘤和肾细胞癌。

Atezolizumab[21],Durvalumab[22]和Avelumab[23]都是针对PD-L1的IgG1单克隆抗体。自2016年来,Atezolizumab和Durvalumab均被批准用于治疗NSCLC和尿路上皮癌,Avelumab被批准用于治疗默克尔细胞癌和尿路上皮癌。

3 ICI主要副作用——免疫相关不良事件ICI通过阻断ICR与配体结合而解除对效应T细胞的抑制,提高其抗肿瘤免疫作用;然而,ICI在通过非特异性免疫激活而杀伤肿瘤的同时,也可能攻击全身各个脏器,导致一系列免疫相关不良事件(immune-related adverse events, irAEs)。irAEs可表现为全身性或器官特异性,常累及皮肤、胃肠道、肺、内分泌腺、肌肉骨骼等,而心血管、肾脏、眼、神经系统的irAEs相对少见[24]。尽管一般情况下ICI引起的irAEs程度较轻且可逆,但如果出现严重的肺炎、结肠炎、心肌炎、脑炎等并发症时可危及生命。

ICI引起irAEs的具体机制尚未明确,一般认为与阻断ICR后免疫稳态的破坏有关:①ICI阻断T细胞上的ICR导致T细胞功能过度上调,攻击正常组织[25];②肿瘤细胞和正常组织上表达的抗原有交叉,ICI与正常组织的ICR(如垂体组织上的CTLA-4)结合后激活补体系统,从而产生免疫病理损伤[26];③ICI可能导致自身抗体(如甲状腺抗体、抗核抗体等)增加,引起自身免疫反应[27];④ICI可导致炎性细胞因子的释放(如IL-17等),且细胞因子水平与irAEs的严重程度呈正相关[28]。irAEs的本质是免疫系统异常激活导致的非特异性免疫病理损伤,因此常需要糖皮质激素、肿瘤坏死因子α (tumor necrosis factor-α, TNF-α)抑制剂或其他免疫抑制剂进行治疗。

4 ICI相关的感染ICI能够促进T细胞激活、增强效应T细胞功能,理论上不会增加感染的易感性,且目前没有证据表明ICI直接导致感染的风险增加。然而,使用ICI后出现感染的病例报告或回顾性研究并不少见,如Nivolumab治疗的肺腺癌患者出现水痘-带状疱疹病毒(varicella zoster virus, VZV)感染[29],Pembrolizumab治疗的黑色素瘤患者出现播散性芽生菌病[30],Atezolizumab治疗的尿路上皮癌患者出现脓毒症[31]等,尽管这些研究未明确ICI与感染的相关性,但是ICI相关的感染却因此逐渐受到重视。

4.1 ICI相关免疫抑制继发感染 4.1.1 使用免疫抑制剂治疗irAEs研究显示,使用免疫抑制剂治疗ICI引起的irAEs可增加继发感染的风险,例如接受Ipilimumab治疗的黑色素瘤患者由于出现irAEs而使用糖皮质激素或TNF-α抑制剂治疗后继发巨细胞病毒性肝炎[32]、肺孢子菌肺炎(pneumocystis pneumonia, PCP)等[33]机会性感染。一项评估748例接受ICI治疗的黑色素瘤患者出现感染的回顾性研究显示[34],严重感染包括细菌性肺炎、腹腔感染、艰难梭菌相关性腹泻、侵袭性肺曲霉病(invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, IPA)、PCP、巨细胞病毒性结肠炎等。主要危险因素是使用糖皮质激素或TNF-α抑制剂,这类患者发生严重感染的比例为13.5%,而在那些没有接受免疫抑制治疗的患者中仅为2%;与单药治疗者相比,接受Ipilimumab和Nivolumab联合治疗者感染率更高,可能是因为联合用药后irAEs的发生率增加,从而对进一步免疫抑制治疗的需求增加,提示ICI相关感染的风险与治疗irAEs的免疫抑制剂的使用高度相关。

因免疫抑制治疗ICI导致的irAEs是并发感染的主要危险因素,建议使用ICI治疗前先对机会性感染的病原体进行筛查[35],并用生物标志物预测irAEs,对高危人群进行预防以减少机会性感染的发生[26]。在irAEs发病初期,考虑使用新型细胞因子靶向药物以尽早抑制快速进展的病理损伤,缩短免疫抑制病程从而降低感染风险[36]。使用免疫抑制剂治疗irAEs时,可采取一定的预防感染措施,如预防PCP或VZV感染。

4.1.2 ICI导致血细胞减少与传统的细胞毒性化疗药物相比,ICI导致骨髓抑制的风险明显要小,但仍有部分患者使用ICI后出现血细胞减少症状。一项研究Nivolumab和Docetaxel(一种化疗药物)治疗NSCLC的随机对照试验发现,使用两种药物的患者出现淋巴细胞减少症的比例分别为1%和6%,中性粒细胞减少症的比例分别为1%和33%[37]。另外,ICI治疗时也会出现再生障碍性贫血(aplastic anemia, AA)[38-40],其中一名患者的骨髓中发现了T细胞浸润[39],提示ICI通过增强效应T细胞功能而杀伤骨髓造血干细胞,也可能由于T细胞活化而引起针对外周血细胞的自身免疫反应,最终导致相应的血细胞减少。出现血细胞减少症可并发感染,例如:使用Nivolumab治疗的胶质母细胞瘤患者出现AA后并发卡他莫拉菌菌血症[39];另一位使用Nivolumab治疗黑色素瘤的患者出现中性粒细胞减少症后死于感染性休克[41],提示ICI可通过减少白细胞从而降低患者的抗感染能力,进而导致机会性感染。因此,监测全血细胞计数对于使用ICI的患者非常重要,当出现血细胞减少时应及时纠正并酌情进行预防性抗感染治疗。

4.1.3 ICI相关糖尿病继发感染一项评估167名接受Nivolumab治疗的NSCLC患者出现感染并发症的回顾性研究发现[42]:19.2%患者出现感染,包括细菌性肺炎、肺脓肿、IPA等,其中2型糖尿病是独立危险因素;但是这部分患者接受ICI之前即患有糖尿病,其本身为合并感染的高危人群。既往有研究表明,接受ICI治疗的患者出现1型糖尿病(type 1 diabetes mellitus, T1DM)特异性自身抗体及T1DM特异性CD8+T细胞[43],提示ICI阻断ICR后可导致免疫系统非特异性激活,对胰岛β细胞产生自身免疫反应,从而进一步诱导T1DM。虽然ICI诱导T1DM的病例较罕见,但由于糖尿病是合并感染的独立危险因素,所以在使用ICI的患者中应重视监测和控制血糖,并警惕发生机会性感染的可能。

4.2 ICI引起的免疫过度激活有报道显示,接受Nivolumab或Pembrolizumab治疗而未发生irAEs或无上述免疫抑制症状的患者出现潜伏性结核感染(latent tuberculosis infection, LTBI)的重新激活[44-46],表现为使用PD-1抑制剂后活动性肺结核迅速进展,提示ICI可能通过增强结核特异性T细胞功能而产生过度免疫反应,使潜伏感染激活,类似于人类免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus,HIV)感染者在开始抗反转录病毒治疗时出现的免疫重建炎症综合征(immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, IRIS)。动物实验显示[47],与野生型小鼠相比,PD-1缺陷小鼠感染结核分枝杆菌后肺部炎症反应和坏死更严重、死亡率更高,提示PD-1/PD-L1通路在限制结核引起的免疫病理损伤中有重要作用,解释了PD-1抑制剂导致LTBI暴发的可能机制。

一名合并慢性进行性肺曲霉病(chronic progressive pulmonary aspergillosis, CPPA)的肺腺癌患者因对传统化疗不敏感而更换使用Nivolumab,肿瘤好转的同时出现CPPA进展[48],提示ICI引起免疫功能上调不仅起到了杀伤肿瘤的作用,还对病原微生物产生过度反应从而导致潜伏感染暴发。

5 结语ICI作为一种新型免疫疗法,与传统化疗相比更能改善患者预后且安全性较高,是肿瘤治疗领域中革命性的进展。然而,一系列并发症的出现对ICI在临床中的使用提出了新的挑战,这些并发症主要为ICI所致的irAEs,以及随之而来的机会性感染,但ICI与感染的相关性和机制尚不明确。尽管有一些指南在临床实践中有重要的指导意义,但推荐的证据级别较低,未来应设计更多前瞻性实验来评估ICI与感染性疾病的关系,并探究其内在机制,进一步优化诊疗流程,在提高治疗效果的同时降低毒副作用,以造福更多肿瘤患者。

| [1] |

Vinay DS, Ryan EP, Pawelec G, Talib WH, Stagg J, Elkord E, Lichtor T, Decker WK, Whelan RL, Kumara H, Signori E, Honoki K, Georgakilas AG, Amin A, Helferich WG, Boosani CS, Guha G, Ciriolo MR, Chen S, Mohammed SI, Azmi AS, Keith WN, Bilsland A, Bhakta D, Halicka D, Fujii H, Aquilano K, Ashraf SS, Nowsheen S, Yang X, Choi BK, Kwon BS. Immune evasion in cancer: mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2015, 35(Suppl): S185-S198.

[URI]

|

| [2] |

Ledford H, Else H, Warren M. Cancer immunologists scoop medicine Nobel prize[J]. Nature, 2018, 562(7725): 20-21.

[PubMed]

|

| [3] |

Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2012, 12(4): 252-264.

[DOI]

|

| [4] |

Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion[J]. Science, 2011, 331(6024): 1565-1570.

[DOI]

|

| [5] |

Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy[J]. Cancer Discov, 2018, 8(9): 1069-1086.

[DOI]

|

| [6] |

Sasidharan Nair V, Elkord E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy: a focus on T-regulatory cells[J]. Immunol Cell Biol, 2018, 96(1): 21-33.

[DOI]

|

| [7] |

Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2008, 26: 677-704.

[DOI]

|

| [8] |

Friedline RH, Brown DS, Nguyen H, Kornfeld H, Lee J, Zhang Y, Appleby M, Der SD, Kang J, Chambers CA. CD4+ regulatory T cells require CTLA-4 for the maintenance of systemic tolerance[J]. J Exp Med, 2009, 206(2): 421-434.

[DOI]

|

| [9] |

Qureshi OS, Zheng Y, Nakamura K, Attridge K, Manzotti C, Schmidt EM, Baker J, Jeffery LE, Kaur S, Briggs Z, Hou TZ, Futter CE, Anderson G, Walker LSK, Sansom DM. Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4[J]. Science, 2011, 332(6029): 600-603.

[DOI]

|

| [10] |

Wang XB, Fan ZZ, Anton D, Vollenhoven AV, Ni ZH, Chen XF, Lefvert AK. CTLA4 is expressed on mature dendritic cells derived from human monocytes and influences their maturation and antigen presentation[J]. BMC Immunol, 2011, 12: 21.

[DOI]

|

| [11] |

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L, Carcereny E, Ahn MJ, Felip E, Lee JS, Hellmann MD, Hamid O, Goldman JW, Soria JC, Dolled-Filhart M, Rutledge RZ, Zhang J, Lunceford JK, Rangwala R, Lubiniecki GM, Roach C, Emancipator K, Gandhi L; KEYNOTE-001 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(21): 2018-2028.

[DOI]

|

| [12] |

Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, Dummer R, Smylie M, Rutkowski P, Ferrucci PF, Hill A, Wagstaff J, Carlino MS, Haanen JB, Maio M, Marquez-Rodas I, McArthur GA, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Grossmann K, Sznol M, Dreno B, Bastholt L, Yang A, Rollin LM, Horak C, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(1): 23-34.

[DOI]

|

| [13] |

Rosenwald A, Wright G, Leroy K, Yu X, Gaulard P, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, Zhao T, Haioun C, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Lynch JC, Vose J, Armitage JO, Smeland EB, Kvaloy S, Holte H, Delabie J, Campo E, Montserrat E, Lopez-Guillermo A, Ott G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Connors JM, Braziel R, Grogan TM, Fisher RI, Miller TP, LeBlanc M, Chiorazzi M, Zhao H, Yang L, Powell J, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES, Simon R, Klausner RD, Staudt LM. Molecular diagnosis of primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma identifies a clinically favorable subgroup of diffuse large B cell lymphoma related to Hodgkin lymphoma[J]. J Exp Med, 2003, 198(6): 851-862.

[DOI]

|

| [14] |

Patsoukis N, Brown J, Petkova V, Liu F, Li L, Boussiotis VA. Selective effects of PD-1 on Akt and Ras pathways regulate molecular components of the cell cycle and inhibit T cell proliferation[J]. Sci Signal, 2012, 5(230): ra46.

[DOI]

|

| [15] |

Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, Lennon VA, Celis E, Chen L. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion[J]. Nat Med, 2002, 8(8): 793-800.

[DOI]

|

| [16] |

Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells[J]. J Exp Med, 2009, 206(13): 3015-3029.

[DOI]

|

| [17] |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. YERVOY©(ipilimumab) highlights of prescribing information[S/OL]. Princeton: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, 2020: (2020-03). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125377s108lbl.pdf.

|

| [18] |

Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, Weber JS, Margolin K, Hamid O, Patt D, Chen T-T, Berman DM, Wolchok JD. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase ii and phase iii trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2015, 33(17): 1889-1894.

[DOI]

|

| [19] |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. KEYTRUDA© (pembrolizumab) Highlights of Prescribing Information[S/OL]. Whitehouse Station: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., 2020: (2020-01). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125514s067lbl.pdf.

|

| [20] |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. OPDIVO© (nivolumab) Highlights of Prescribing Information[S/OL]. Princeton: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, 2020: (2020-03). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125554s078lbl.pdf.

|

| [21] |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. TECENTRIQ© (atezolizumab) Highlights of Prescribing Information[S/OL]. South San Francisco: Genentech, Inc., 2019: (2019-12). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761034s021lbl.pdf.

|

| [22] |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. IMFINZI© (durvalumab) Highlights of Prescribing Information[S/OL]. Wilmington: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, 2020: (2020-03). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761069s018lbl.pdf.

|

| [23] |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. BAVENCIO© (avelumab) Highlights of Prescribing Information[S/OL]. Rockland: EMD Serono, Inc., 2019: (2019-05). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761049s006lbl.pdf.

|

| [24] |

Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 378(2): 158-168.

[DOI]

|

| [25] |

June CH, Warshauer JT, Bluestone JA. Is autoimmunity the Achilles' heel of cancer immunotherapy[J]. Nat Med, 2017, 23(5): 540-547.

[DOI]

|

| [26] |

Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, Berdelou A, Varga A, Bahleda R, Hollebecque A, Massard C, Fuerea A, Ribrag V, Gazzah A, Armand JP, Amellal N, Angevin E, Noel N, Boutros C, Mateus C, Robert C, Soria JC, Marabelle A, Lambotte O. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2016, 54: 139-148.

[DOI]

|

| [27] |

Osorio JC, Ni A, Chaft JE, Pollina R, Kasler MK, Stephens D, Rodriguez C, Cambridge L, Rizvi H, Wolchok JD, Merghoub T, Rudin CM, Fish S, Hellmann MD. Antibody-mediated thyroid dysfunction during T-cell checkpoint blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2017, 28(3): 583-589.

[DOI]

|

| [28] |

Tarhini AA, Zahoor H, Lin Y, Malhotra U, Sander C, Butterfield LH, Kirkwood JM. Baseline circulating IL-17 predicts toxicity while TGF-β1 and IL-10 are prognostic of relapse in ipilimumab neoadjuvant therapy of melanoma[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2015, 3: 39.

[DOI]

|

| [29] |

Gozzi E, Rossi L, Angelini F, Leoni V, Trenta P, Cimino G, Tomao S. Herpes zoster granulomatous dermatitis in metastatic lung cancer treated with nivolumab: a case report[J]. Thorac Cancer, 2020, 11(5): 1330-1333.

[DOI]

|

| [30] |

Ferguson I, Heberton M, Compton L, Keller J, Cornelius L. Disseminated blastomycosis in a patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma[J]. JAAD Case Rep, 2019, 5(7): 580-581.

[DOI]

|

| [31] |

Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Balar AV, Necchi A, Dawson N, O'Donnell PH, Balmanoukian A, Loriot Y, Srinivas S, Retz MM, Grivas P, Joseph RW, Galsky MD, Fleming MT, Petrylak DP, Perez-Gracia JL, Burris HA, Castellano D, Canil C, Bellmunt J, Bajorin D, Nickles D, Bourgon R, Frampton GM, Cui N, Mariathasan S, Abidoye O, Fine GD, Dreicer R. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10031): 1909-1920.

[DOI]

|

| [32] |

Uslu U, Agaimy A, Hundorfean G, Harrer T, Schuler G, Heinzerling L. Autoimmune colitis and subsequent CMV-induced hepatitis after treatment with ipilimumab[J]. J Immunother, 2015, 38(5): 212-215.

[DOI]

|

| [33] |

Arriola E, Wheater M, Krishnan R, Smart J, Foria V, Ottensmeier C. Immunosuppression for ipilimumab-related toxicity can cause pneumocystis pneumonia but spare antitumor immune control[J]. Oncoimmunology, 2015, 4(10): e1040218.

[DOI]

|

| [34] |

Del Castillo M, Romero FA, Argüello E, Kyi C, Postow MA, Redelman-Sidi G. The spectrum of serious infections among patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade for the treatment of melanoma[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2016, 63(11): 1490-1493.

[DOI]

|

| [35] |

Thompson JA, Schneider BJ, Brahmer J, Andrews S, Armand P, Bhatia S, Budde LE, Costa L, Davies M, Dunnington D, Ernstoff MS, Frigault M, Kaffenberger BH, Lunning M, McGettigan S, McPherson J, Mohindra NA, Naidoo J, Olszanski AJ, Oluwole O, Patel SP, Pennell N, Reddy S, Ryder M, Santomasso B, Shofer S, Sosman JA, Wang Y, Weight RM, Johnson-Chilla A, Zuccarino-Catania G, Engh A. NCCN guidelines insights: management of immunotherapy-related toxicities, version 1[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2020, 18(3): 230-241.

[DOI]

|

| [36] |

Martins F, Sykiotis GP, Maillard M, Fraga M, Ribi C, Kuntzer T, Michielin O, Peters S, Coukos G, Spertini F, Thompson JA, Obeid M. New therapeutic perspectives to manage refractory immune checkpoint-related toxicities[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2019, 20(1): e54-e64.

[DOI]

|

| [37] |

Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, Waterhouse D, Ready N, Gainor J, Aren Frontera O, Havel L, Steins M, Garassino MC, Aerts JG, Domine M, Paz-Ares L, Reck M, Baudelet C, Harbison CT, Lestini B, Spigel DR. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(2): 123-135.

[DOI]

|

| [38] |

Helgadottir H, Kis L, Ljungman P, Larkin J, Kefford R, Ascierto PA, Hansson J, Masucci G. Lethal aplastic anemia caused by dual immune checkpoint blockade in metastatic melanoma[J]. Ann Oncol, 2017, 28(7): 1672-1673.

[DOI]

|

| [39] |

Comito RR, Badu LA, Forcello N. Nivolumab-induced aplastic anemia: A case report and literature review[J]. J Oncol Pharm Pract, 2019, 25(1): 221-225.

[DOI]

|

| [40] |

Filetti M, Giusti R, Di Napoli A, Iacono D, Marchetti P. Unexpected serious aplastic anemia from PD-1 inhibitors: beyond what we know[J]. Tumori, 2019, 105(6): NP48-NP51.

[DOI]

|

| [41] |

Delanoy N, Michot JM, Comont T, Kramkimel N, Lazarovici J, Dupont R, Champiat S, Chahine C, Robert C, Herbaux C, Besse B, Guillemin A, Mateus C, Pautier P, SaÏag P, Madonna E, Maerevoet M, Bout JC, Leduc C, Biscay P, Quere G, Nardin C, Ebbo M, Albigès L, Marret G, Levrat V, Dujon C, Vargaftig J, Laghouati S, Croisille L, Voisin AL, Godeau B, Massard C, Ribrag V, Marabelle A, Michel M, Lambotte O. Haematological immune-related adverse events induced by anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy: a descriptive observational study[J]. Lancet Haematol, 2019, 6(1): e48-e57.

[DOI]

|

| [42] |

Fujita K, Kim YH, Kanai O, Yoshida H, Mio T, Hirai T. Emerging concerns of infectious diseases in lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy[J]. Respir Med, 2019, 146: 66-70.

[DOI]

|

| [43] |

Byun DJ, Wolchok JD, Rosenberg LM, Girotra M. Cancer immunotherapy-immune checkpoint blockade and associated endocrinopathies[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2017, 13(4): 195-207.

[URI]

|

| [44] |

Lee JJ, Chan A, Tang T. Tuberculosis reactivation in a patient receiving anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor for relapsed Hodgkin's lymphoma[J]. Acta Oncol, 2016, 55(4): 519-520.

[DOI]

|

| [45] |

Picchi H, Mateus C, Chouaid C, Besse B, Marabelle A, Michot JM, Champiat S, Voisin AL, Lambotte O. Infectious complications associated with the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in oncology: reactivation of tuberculosis after anti PD-1 treatment[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2018, 24(3): 216-218.

[DOI]

|

| [46] |

Chu YC, Fang KC, Chen HC, Yeh YC, Tseng CE, Chou TY, Lai CL. Pericardial tamponade caused by a hypersensitivity response to tuberculosis reactivation after anti-PD-1 treatment in a patient with advanced pulmonary adenocarcinoma[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2017, 12(8): e111-e4.

[DOI]

|

| [47] |

Lázár-Molnár E, Chen B, Sweeney KA, Wang EJ, Liu W, Lin J, Porcelli SA, Almo SC, Nathenson SG, Jacobs WR Jr. Programmed death-1 (PD-1)-deficient mice are extraordinarily sensitive to tuberculosis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010, 107(30): 13402-13407.

[DOI]

|

| [48] |

Uchida N, Fujita K, Nakatani K, Mio T. Acute progression of aspergillosis in a patient with lung cancer receiving nivolumab[J]. Respirol Case Rep, 2018, 6(2): e00289.

[DOI]

|

2021, Vol. 16

2021, Vol. 16