2. 复旦大学上海医学院基础医学院教育部/卫健委/中国医科院医学分子病毒学重点实验室, 上海 200032;

3. 堪培拉大学, 澳大利亚首都直辖区 2617, 澳大利亚

2. Key Laboratory of Medical Molecular Virology (MOE/NHC/CAMS), School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China;

3. University of Canberra, Australia Capital Territory 2617, Australia

乙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis B virus,HBV)感染是一个全球性的公共卫生问题,全世界有超过2.4亿慢性HBV感染者。慢性乙型肝炎(chronic hepatitis B,CHB)与肝纤维化、肝硬化和肝癌的风险高度相关,目前仍难以彻底治愈[1]。

多项证据表明,慢性HBV感染过程中循环免疫复合物(circulating immune complex,CIC)的形成及下游补体经典信号通路的激活是造成肝内、肝外损害的重要因素之一[2]。CIC的大小受免疫球蛋白亲和力、反应温度、抗原抗体比例等因素的影响,相对分子质量较大的CIC更容易沉积在血管系统中,从而导致相关器官受到损害[3]。在登革病毒、巨细胞病毒、肝炎病毒等感染导致的疾病进展过程中,CIC的形成可诱发一系列相关疾病[4]。既有研究表明,在HBV感染过程中,机体存在活跃的体液免疫反应,患者体内成熟、未成熟的病毒颗粒及病毒相关分子可在一定条件下与抗体结合,形成大量CIC[5-8]。1969年,有研究者通过电子显微镜观察到CHB患者血液中存在大量以免疫复合物形式存在的病毒颗粒[6]。多项研究表明,在急性和慢性HBV感染患者中均可检测到大量CIC产生,而HBV携带者和健康人中的CIC含量极低[4, 6]。

通常情况下,CIC与补体结合,然后通过与红细胞、中性粒细胞、血小板表面的补体受体结合[3, 9],输送至肝脏或脾脏,最后经Kupffer细胞等清除[10]。当CIC大量存在时,会在组织、神经、血管、滑膜的细胞表面沉积[11]。其中IgG、IgM免疫复合物可与补体信号分子C1q相互作用[12],进一步激活补体经典信号通路。在肝外,这种CIC的沉积会在血小板、中性粒细胞等参与下引发Ⅲ型超敏反应,造成充血水肿、局部坏死,甚至导致肝外损伤。约16%的CHB患者有临床肝外表现[13],包括风湿性疾病、肾小球肾炎、干燥综合征、肌痛、关节炎等[14]。在肝内,肝实质细胞、Kupffer细胞、星形细胞和窦状内皮细胞共同组成了肝脏微环境。其中,肝窦内皮细胞和Kupffer细胞表达补体受体,参与CIC的清除[10, 15]。虽然目前尚无研究直接报道病毒导致的肝脏炎症和纤维化与CIC清除、补体激活之间的联系,但多项证据提示后两者在炎症和纤维化的过程中发挥了重要作用。例如,有研究发现,在HBV及丙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis C virus,HCV)感染过程中,Kupffer细胞表面的补体受体被激活后,可进一步触发包括肿瘤坏死因子α(tumor necrosis factor α,TNF-α)和白细胞介素6(interleukin 6,IL-6)在内的促炎细胞因子释放[16]。在HBV导致的肝炎,尤其是急性重型肝炎患者肝坏死区周围的肝细胞表面,可观察到膜攻击复合物[17]。近年来的研究进一步证实,急性重型肝炎患者体内存在大量针对HBV核心抗原(HBV core antigen,HBcAg)的免疫复合物,其形成激活了补体经典信号通路,导致肝细胞大量坏死[7]。一项针对补体经典信号通路产物C4d的染色研究表明,有89%的CHB患者呈C4d阳性[18]。此外,在HBV感染的急性阶段,血液中的补体通常被消耗[19],这种消耗在其他疾病如系统性红斑狼疮(systemic lupus erythematosus,SLE)中,可引起CIC在血液循环中滞留,引发后续更强的机体损伤[20]。以上证据均支持CIC激活的补体经典信号通路与CHB患者肝脏炎症密切相关。然而,CHB患者中CIC的形成与肝脏炎症及纤维化、血清中补体成分之间的关系仍有待进一步研究。

目前,CIC的常用检测方法主要包括以下几类:①利用连续培养的Raji细胞系通过Fc受体结合可溶性CIC[21];②基于增加的分子大小,利用聚乙二醇[poly(ethylene glycol),PEG]沉淀对CIC进行分离[22];③利用补体或特定抗人抗体与CIC结合,采用放射免疫分析法、免疫荧光法等对CIC进行分析[23-25]。

为探讨CHB患者体内的CIC水平并在临床队列中进行分析,本研究借鉴了一种高效、灵敏的固相C1q结合荧光免疫法(solid-phase Clq-binding fluorescence immunoassay)[25]。C1q是补体经典信号通路中的靶识别蛋白,在血清中与Clr2-Cls2形成四聚体,共同构成补体经典信号通路的第一成分C1,在连接特异性免疫和非特异性免疫中起重要作用。C1q包含一个N端胶原样区和一个C端球状结构域,后者的球状头部gC1q通过四级交互作用与CIC表面的抗体Fc段特异性结合,从而触发补体经典信号通路[26]。在检测过程中,将C1q包被在聚苯乙烯板板底,利用C1q特异性结合CIC的特点,将荧光标记的羊抗人IgG(Fab)2作为荧光信号来源,采用荧光酶标仪对血液中的CIC进行定量[25]。在早期,该方法主要用于SLE等自身免疫性疾病的检测。本研究对该方法在CHB患者中的应用进行了验证及优化,并检测了220例CHB患者的血清CIC水平,旨在探讨CIC与CHB诊断所用病毒学指标、生化指标之间的相关性,从而揭示CIC与CHB病程进展的潜在关联。

1 材料和方法 1.1 材料 1.1.1 研究对象用于CIC检测方法建立的临床样本来自上海市公共卫生临床中心肝胆内科的40例高HBV DNA载量(均>107IU/mL)CHB患者,收录信息包括HBV e抗原(HBV e antigen,HBeAg)、丙氨酸转氨酶(alanine aminotransferase,ALT)、HBV表面抗原(HBV surface antigen,HBsAg)、HBV核心抗体(HBV core antibody,HBcAb)等。用于CIC临床意义探索的临床样本来自上海市公共卫生临床中心肝胆内科2015—2017年收治的220例CHB患者、10例CHB功能性治愈者、20例非乙型肝炎的肝炎患者。其中,220例CHB患者的收录信息包括人口学特征、常用血清肝功能生化指标、免疫学指标、乙型肝炎诊断常用血清标记、血常规指标、肝穿炎症评分(Scheuer grade)、肝穿纤维化评分(fibrosis staging score)等临床信息。用于临床意义探索的样本来源均未合并感染其他病毒,且排除了有先天性或继发性疾病者(如药物性肝炎、酒精性肝炎、原发性胆汁性肝硬化等)以及影像学确诊有肿瘤者。所有CHB患者均为初治患者,功能性治愈者的HBV DNA均低于检测下限,HBsAg均为阴性。所有患者的CHB诊断符合2019版《慢性乙型肝炎防治指南》的标准。

1.1.2 样本收集及检测将入组患者的静脉血置于-80 ℃保存。采用美国Abbott ARCHITECT i2000对HBsAg、HBeAg进行化学发光微粒免疫分析(chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay),采用美国ABI 7500对血清HBV DNA进行聚合酶链反应(polymerase chain reaction,PCR)-荧光探针法(fluorescence probing assay)定量,HBcAb的定量由北京万泰生物药业股份有限公司完成。血清补体C3、C4的检测采用西门子BN Ⅱ全自动蛋白分析仪,通过免疫散射比浊法检测。血清ALT、AST采用Abbott Architect C16000全自动生化分析系统及其配套试剂检测。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 固相C1q结合荧光免疫法使用促凝管采集待检血清样本并分离,储存于-80 ℃冰箱。检测时,将购自CompTech公司的C1q(C1q protein in 40% glycerol)稀释至10 μg/mL(稀释液为0.1 mol/L NaHCO3,pH值=9.2),按100 μL/孔加入96孔避光板,于4 ℃孵育12 h以上。弃去C1q,用2%牛血清白蛋白(bovine serum albumin,BSA)室温封闭2 h。将稀释后的(稀释液为0.2% BSA)标准品和血清或血浆样本添加到C1q包被的聚苯乙烯板孔中,于37 ℃孵育1 h。所加样品均须在解冻后进行充分混匀。此外,为了排除样品与包被物中的其他成分的非特异性结合,利用高盐离子稀释液能够抑制C1q的结合能力这一特点,将1 mol/L NaCl作为稀释液稀释样本,以作为对照。然后,待测孔每孔加入由Alexa Fluor 488标记的山羊抗人IgG(Fab)2(Jackson ImmunoResearch 109-546-097)(1∶2 000稀释)100 μL,37 ℃避光孵育40 min后彻底清洗。采用荧光酶标仪(VICTOR3,PerkinElmer)读取荧光值,在程序Wallac 1420 Manager,485 nm/535 nm,1.0 s设定下测定总免疫复合物的含量。将所得荧光值通过标准曲线转换为CIC浓度。

1.2.2 CIC检测标准曲线绘制采用NanoDrop超微量分光光度计测定乙型肝炎免疫球蛋白(hepatitis B immunoglobulin,HBIG)原液浓度后,用磷酸盐缓冲液(phosphate buffered saline,PBS)将HBIG稀释至30 mg/mL,于63 ℃金属浴中加热30 min,使其变性聚合,15 000 g离心20 min。去除上清液,取下层沉淀加入PBS重悬,再次测定浓度后,稀释至200 μg/mL,并进一步梯度稀释为25 μg/mL、12.5 μg/mL、6.25 μg/mL、3.125 μg/mL、1.56 μg/mL,与样本在同一块96孔避光板中孵育,利用GraphPad Prism 8.0生成线性标准曲线。

1.3 统计学分析利用GraphPad Prism 8.0和MedCalc 15.8进行数据统计分析并作图,P < 0.05代表差异有统计学意义。将HBV DNA、HBsAg、HBcAb均转换为对数形式,采用Spearman相关性分析探讨CIC与CHB诊断所用病毒学指标、肝功能生化指标及分类变量(炎症、纤维化评级)之间的相关性,采用Mann-Whitney U检验比较不同分类下患者之间CIC水平的差异,通过Kruskal-Wallis检验比较不同临床分期患者之间总免疫复合物的差异,两两之间比较采用Dunn's test for multiple comparison。截断值的划分采用阴性样本(健康人血清)的平均值+2×阴性样本SD值。

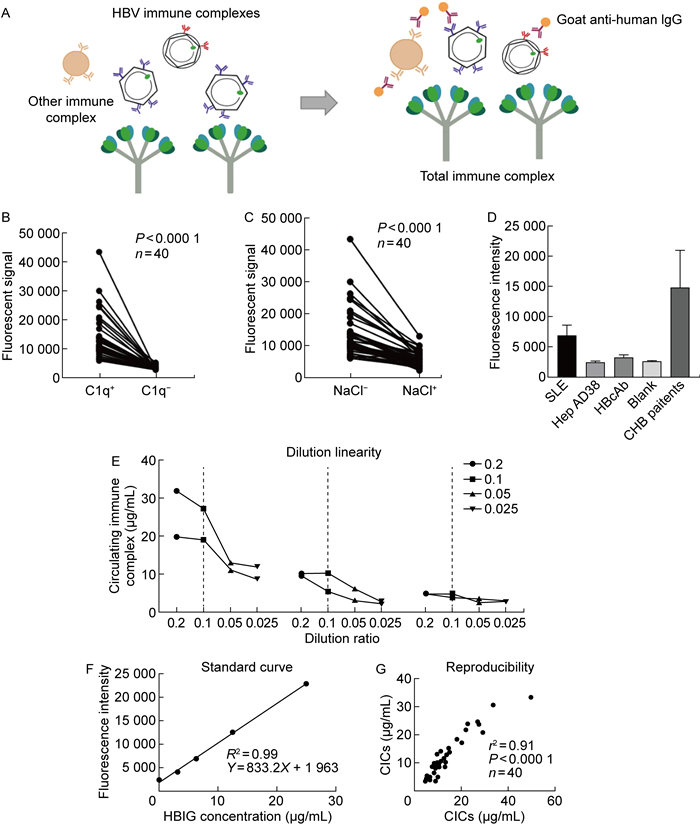

2 结果 2.1 CIC检测方法的原理及特异性固相C1q结合荧光免疫法的基本原理及流程如图 1A所示。将C1q通过吸附作用包被在聚苯乙烯板底,加入样品后即可特异性捕获CIC。利用荧光标记的羊抗人IgG(Fab)2与CIC表面的抗体结合,通过荧光信号对免疫复合物进行定量。

|

| A: The principle of solid-phase C1q-binding fluorescence immunoassay. B: C1q was not coated to the wells to exclude non-specific binding of CICs to polystyrene surface. 40 CHB patients were tested. The non-specific binding of immune complexes, fluorescent-labeled antibody to the uncoated wells was much lower than specific capture ability of C1q-coated wells (P < 0.000 1). C: The specimen (from 40 CHB patients) were diluted in high salt concentration diluent (1 mol/L NaCl), which was known to inhibit the binding ability of C1q to CICs. The signal in NaCl diluting group (shown as NaCl+ in histogram) was much lower than that in 0.2% BSA diluting group (NaCl-) (P < 0.000 1). D: To exclude the interference of free antibodies and antigens, the condensed HepAD38 cell supernatants and HBcAb were tested as controls. The fluorescence intensities in HepAD38 cell and HBcAb groups were much lower than that in the SLE patients (P < 0.000 1) and had no significant difference compared with the blank control. E: The dilution linearity of solid-phase C1q-binding fluorescence immunoassay. The dotted line showed the best dilution ratio of the test (10×). F: The standard curve constructed by heat aggregated HBIG. G: The reproducibility of solid-phase C1q-binding fluorescence immunoassay was tested by Spearman correlation analysis. 图 1 C1q与CIC结合的特异性、线性、标准曲线及可重复性测试 Fig. 1 Specificity, linearity, standard curve and reproducibility of CICs binding to C1q |

本研究首先对固相C1q结合荧光免疫法在CHB患者中应用的可行性进行了验证。为保证结果的阳性率,在方案验证过程中共检测了40例具有高HBV DNA载量(>107IU/mL)的CHB患者血清,其临床信息如表 1所示。

| Item | CHB patients (n=40) |

| Gender (male: female) | 19:21 |

| Age (years) | 29.22(26.32, 32.13) |

| Serum HBsAg (lg IU/mL) | 4.59(4.47, 4.71) |

| Serum anti-HBc (S/CO) | 8.29(4.10, 10.10) |

| Serum HBV DNA (lg IU/mL) | 8.43(7.32, 8.54) |

| Serum HBeAg (lg IU/mL) | 2.93(2.77, 3.10) |

| Serum indexes were shown as median (95% confidence interval). Age data were shown as M(IQR); M, mean; IQR, interquartile range. | |

为排除CIC、荧光抗体与聚苯乙烯板间的非特异性吸附,实验设置了C1q包被孔与无C1q包被的对照孔,同时进行荧光抗体的孵育及信号检测。结果如图 1B所示,无C1q包被孔中仅存在较弱的荧光信号,显著低于C1q包被孔(P < 0.000 1),表明CHB患者血液中CIC及荧光抗体仅有极少量非特异性吸附于聚苯乙烯板。

为进一步验证C1q与CIC的特异性结合,将高盐浓度稀释液(1 mol/L NaCl)用于样本稀释。结果如图 1C所示,高浓度盐离子组样本的荧光信号显著降低(P < 0.000 1),表明高浓度盐离子显著抑制了C1q的结合能力,高信号值孔内存在C1q与CIC的特异性结合。

为排除游离抗原和抗体对荧光信号的干扰,将HepAD38细胞培养上清液和HBcAb分别作为对照,与4例SLE患者样本一同检测。结果如图 1D所示,HepAD38细胞上清液中的游离抗原和游离HBcAb与C1q仅存在少量结合,显著低于SLE患者样本(P < 0.000 1),且与空白孔无显著性差异。

此后,为确认合适的样品稀释比例,使用连续稀释的SLE患者血清、CHB患者血清、正常对照者血清,以测试该方法的线性度(40倍、20倍、10倍和5倍稀释)。结果如图 1E所示,40倍、20倍、10倍稀释后,荧光信号均呈线性下降,后续研究中将10倍稀释作为样品的稀释比例。

为进一步准确定量CIC的荧光信号,对HBIG进行加热处理使其聚合,然后进行梯度稀释,绘制标准曲线。结果如图 1F所示,该检测方案的线性范围为0~25 μg/mL。线性回归分析显示,在该范围内的标准曲线显示出良好的线性(R2=0.99)。

基于以上结果,为确认方案的可重复性,本研究进一步检测了40例CHB患者的血清样品,利用标准曲线将其荧光值进行换算。Spearman相关性分析显示,该检测方法有良好的可重复性(r=0.91,P < 0.000 1,见图 1G)。

2.2 临床队列信息及检测质控为分析CIC的临床意义,本研究共纳入不同状态的初治CHB患者220例、CHB功能性治愈者10例(HBsAg阴性,且HBV DNA低于检测下限)、非乙型肝炎的肝炎患者20例(慢性丙型肝炎7例、非病毒性肝炎13例)、SLE患者4例、健康体检者20例。

为确保研究结果的特异性和可比性,在同一批实验中完成了所有入组样本的CIC检测,且96孔板均相应分配了相同数量的HBV e抗原(HBV e antigen,HBeAg)(+)和HBeAg(-)患者样本,并设置了阳性对照(SLE患者样本)、阴性对照(浓缩后的HepAD38细胞培养上清液)、空白对照。详细队列信息如表 2所示。

| Item | HBeAg-positive (n=120) |

HBeAg-negative (n=100) |

Non-HBV hepatitis (n =20) |

Normal people (n=20) |

Recovery (n=10) |

Z*/χ2† value | P value |

| Gender (male: female) | 68:52 | 57:43 | 8:12 | 9:11 | / | 4.158a | 0.886 1 |

| Age (years) | 34.35 (27, 39) | 42.58 (35, 49) | 47.35 (18, 69) | 54.09 (4, 87) | / | 5.699b | < 0.000 1 |

| ALT (U/L) | 146.2 (45.0, 161.2) | 66.77 (20.75, 68.00) | 194 (51.33-202.12) | 14.65 (6, 34) | / | 5.459b | < 0.000 1 |

| AST (U/L) | 88.86 (69.15, 108.56) | 46.04 (36.50, 55.58) | 127.00 (63.92, 190.07) | / | / | 4.920b | < 0.000 1 |

| AKP (U/L) | 84.39 (78.39, 90.39) | 82.45 (77.23, 87.67) | 143.90 (89.97, 197.82) | / | / | 0.543b | 0.587 5 |

| GGT (U/L) | 52.90 (42.60, 63.19) | 46.901 (36.32, 57.49) | 174.80 (81.34, 268.25) | / | / | 1.334b | 0.182 1 |

| TP (g/L) | 69.62 (68.54, 70.70) | 70.62 (69.42, 71.82) | 69.91 (67.38, 72.44) | / | / | 1.343b | 0.179 4 |

| Alb (g/L) | 41.42 (40.76, 42.08) | 42.77 (42.02, 43.52) | 42.81 (39.99, 45.62) | / | / | 3.076b | 0.002 1 |

| Glb (g/L) | 28.25 (27.39, 29.10) | 27.92 (26.98, 28.86) | 27.15 (24.94, 29.35) | / | / | 0.394b | 0.693 2 |

| C3 (g/L) | 0.84 (0.81, 0.88) | 0.90 (0.86, 0.94) | 1.002 5 (0.89, 1.11) | / | / | 2.162b | 0.030 7 |

| C4 (g/L) | 0.16 (0.15, 0.17) | 0.19 (0.17, 0.20) | 0.217 0 (0.18, 0.24) | / | / | 3.401b | 0.000 7 |

| HBsAg (lg IU/mL) | 3.98 (3.49, 4.55) | 3.04 (2.80, 3.59) | - | - | - | 7.874b | < 0.000 1 |

| anti-HBc (lg IU/mL) | 0.975 6 (0.965 7, 1.026 0) | 1.041 5 (0.996 5, 1.058 8) | / | / | / | 11.215b | < 0.000 1 |

| HBV DNA (lg IU/mL) | 6.905 (6.306, 7.830) | 4.485 (3.343, 5.415) | - | - | - | 8.834b | < 0.000 1 |

| Grade (1:2:3:4) | 56:39:5:0c | 80:16:4:0 | 6:8:4:0d | - | / | 17.817a | 0.000 4 |

| Stage (1:2:3:4) | 44:35:8:13c | 61:18:7:14 | 7:5:4:2d | - | / | 20.786a | 0.000 1 |

| Data were expressed as the median (95% confidential interval). * Mann-Whitney U test, †Pearson χ2 test, achi-square test, bKruskall-Wallis analysis, cLack of 20 liver biopsy specimens, d Lack of 2 liver biopsy specimens. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; TP, total protein; Alb, albumin; Glb, globulin. | |||||||

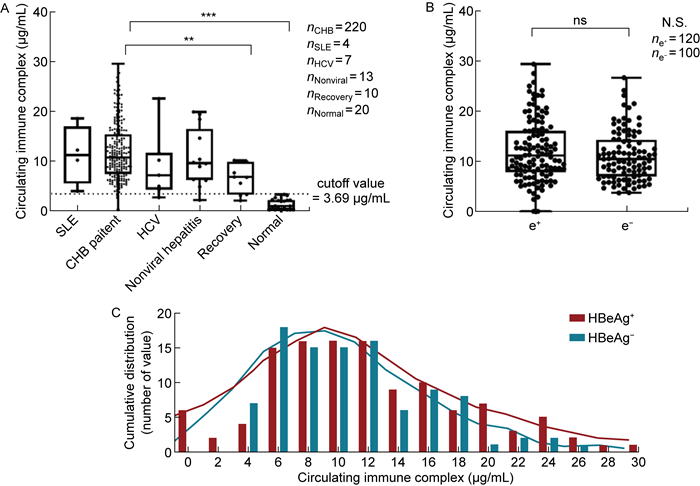

根据健康人血清CIC质量浓度的95%置信区间为CHB患者的CIC质量浓度划定了截断值(CIC≤3.69 μg/mL)。在该队列中,97%的CHB患者CIC质量浓度高于截断值。CHB功能性康复者CIC质量浓度显著低于CHB患者(P=0.002,Dunn's multiple comparison test),但仍显著高于健康人(P < 0.000 1),10例康复者中有7例略高于截断值(见图 2A)。

|

| A: CIC levels among different types of hepatitis patients and normal people. The cutoff value was shown as dotted lines. B: CIC levels in HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients. C: CIC level distribution across the study population (median 10.54 μg/mL, range 0.1-29.44 μg/mL). CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. 图 2 不同类型肝炎患者体内的CIC水平 Fig. 2 CIC levels among different types of hepatitis patients |

HBeAg阳性与阴性患者之间CIC质量浓度无显著性差异(见图 2B)。进一步分析表明,CIC质量浓度在CHB患者中呈偏态分布(中位数10.54 μg/mL,0.1~29.44 μg/mL,Shapiro-Wilk检验)(见图 2C)。

2.4 CIC与CHB诊断常用指标的相关性分析进一步分析CIC与CHB诊断常用指标之间的相关性,包括如下指标。①病毒学指标:HBV DNA、HBcAb、HBsAg。②肝脏损伤相关指标:ALT、天冬氨酸转氨酶(aspartate aminotransferase,AST)、γ-谷氨酰转肽酶(γ-glutamyl transpeptidase,GGT)、碱性磷酸酶(alkaline phosphatase,AKP)。③蛋白质合成指标:总蛋白(total protein,TP)、球蛋白(globulin,Glb)、白蛋白(albumin,Alb)、白/球比(albumin/globulin,A/G)。Spearman相关性分析显示,CIC与HBsAg(r=0.197 3,P=0.005 8)及HBV DNA(r=0.217 8,P=0.002 3)显著正相关,提示CHB患者中CIC的来源与病毒复制的活跃程度有关。另一方面,CIC与肝脏损伤常用指标ALT(r=0.158 0,P=0.020 0)、AST(r=0.151 3,P=0.035 3)亦显著正相关,与体液免疫产物血清Glb高度正相关(r=0.256 3,P=0.000 3),与A/G呈负相关(r=-0.267 1,P=0.000 2),进一步提示C1q可结合血清中的CIC,且CIC相关体液免疫反应与体液免疫激活导致的肝脏损伤有潜在联系(见表 3)。

| Marker | r value | P value | |

| Virological marker | HBsAg (lg IU/mL) | 0.197 3 | 0.005 8 |

| HBcAb (IU/mL) | 0.037 4 | 0.604 6 | |

| HBV DNA (lg IU/mL) | 0.217 8 | 0.002 3 | |

| Inflammatory marker | AST (IU/L) | 0.151 3 | 0.035 3 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 0.158 0 | 0.020 0 | |

| GGT (IU/L) | -0.085 5 | 0.235 9 | |

| AKP (IU/L) | 0.037 2 | 0.606 6 | |

| Protein metabolism marker | TP (g/L) | 0.156 3 | 0.029 6 |

| Alb (g/L) | -0.055 4 | 0.443 1 | |

| Glb (g/L) | 0.256 3 | 0.000 3 | |

| A/G | -0.267 1 | 0.000 2 | |

| Calculated by Spearman correlation analysis. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; TP, total protein; Alb, albumin; Glb, globulin; A/G, albumin/globulin. | |||

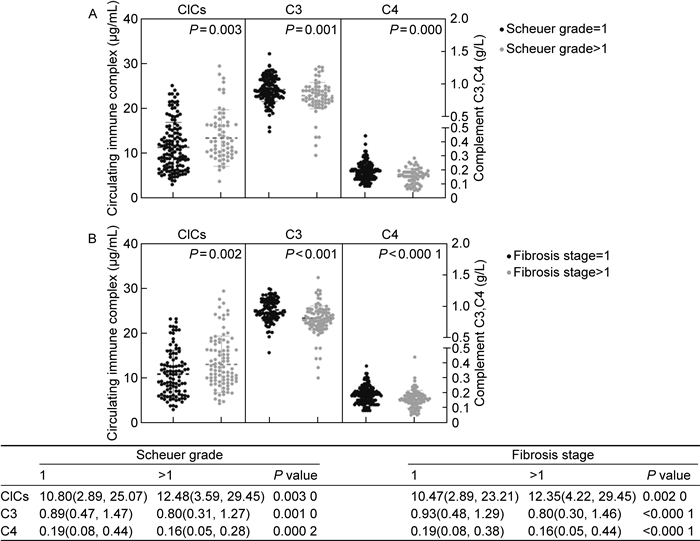

基于以上结果,本研究检测了肝脏存在不同程度炎症和纤维化患者体内的CIC水平。结果如图 3所示,肝脏炎症、纤维化程度较高的患者体内CIC质量浓度显著高于炎症(P=0.003)、纤维化(P=0.002)程度较低的患者,提示CIC的产生和清除过程与肝脏的炎症、纤维化程度有潜在联系。由于HBV感染过程中CIC的清除与补体经典信号通路激活有关,本研究进一步分析了不同程度肝脏炎症和纤维化患者体内补体C3、C4的水平。结果如图 3所示,在肝脏炎症程度较高、纤维化较严重的患者中,其体内补体C3、C4的质量浓度显著低于无明显肝脏炎症(C3:P=0.001;C4:P=0.000 2)、无肝脏纤维化的患者(C3:P < 0.000 1;C4:P < 0.000 1),提示肝脏炎症程度较高、纤维化较严重的患者体内存在补体消耗。对CIC与补体、炎症、纤维化之间的关系进行Spearman相关性分析,结果如图 4所示,CIC与炎症(r=0.20,P=0.005)、纤维化(r=0.18,P=0.011)正相关,与补体C4负相关(r=-0.21,P=0.003)。由此可推测,CHB患者体内CIC的清除可能伴随补体的消耗,且这一过程与肝脏炎症、纤维化有潜在关联。

|

| The levels of CICs, complement C3, complement C4 in the patients with different levels of liver inflammation (A) and fibrosis (B). The CICs, complement C3, complement C4 were grouped according to liver Scheuer grade and fibrosis staging score and were compared by Mann-Whitney U test. The P value, median and 95% confidence intervals (shown in parentheses) were summarized below. 图 3 不同程度肝脏炎症、纤维化患者体内的CICs、C3、C4水平 Fig. 3 Levels of CICs, C3, C4 in patients with different levels of liver inflammation and fibrosis |

|

| The correlation matrix among CICs, complement C3, complement C4, liver inflammation and fibrosis. The P value of each comparison was summarized below. The color indicates the value of Spearman correlation coefficients. Blue indicates positive correlation and red indicates negative correlation. 图 4 CICs、C3、C4、炎症、纤维化的相关性矩阵 Fig. 4 Correlation matrix among CICs, C3, C4, liver inflammation and fibrosis |

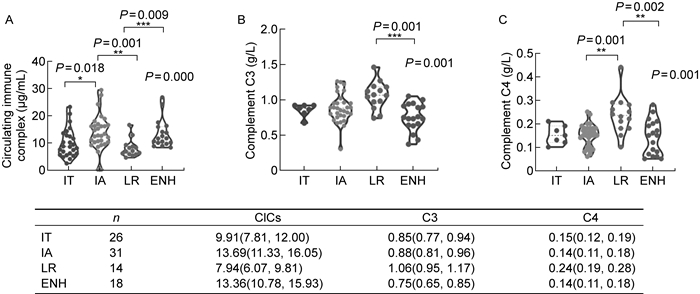

目前,临床上将CHB病程分为4个阶段:免疫耐受期、免疫清除期、免疫控制期、再活动期。本研究对该队列中的慢性肝炎患者进行进一步分期,比较了不同临床分期患者血液循环中的CIC及补体水平。

Kruskal-Wallis检验显示,4个分期患者之间CIC(P=0.000 2)、C3(P=0.001 0)、C4(P=0.001 0)水平均有显著性差异。Dunn's multiple comparisons test两两比较分析结果表明,CIC水平在免疫激活期及再活动期显著高于免疫耐受期和低复制期(见图 5A);血清补体成分C3(见图 5B)、C4(见图 5C)的水平则在低复制期最高,显著高于再活动期和免疫激活期。以上结果进一步表明,CHB患者血清中CIC水平与CHB病程进展有关,其产生会造成补体的消耗,且与肝脏损伤之间存在关联。

|

| Levels of CICs (A), complement C3 (B) and complement C4 (C) throughout the natural history of CHB. Violin plots with dots were drawn in each stage of CHB. Dunn's multiple comparisons test of each group was shown between each group. The difference among all four stages were compared by Kruskal Wallis test and the P value was shown on the top right corner of each plot. The median and 95% confident interval were summarized below. Dunn's multiple comparison test was used for the comparison between each group. IT, immune tolerance; IA, immune active; LR, low replication; ENH, HBeAg-negative hepatitis. 图 5 CHB不同临床分期患者体内的CICs、C3、C4水平 Fig. 5 Levels of CICs, C3, C4 across four stages of CHB patients |

HBV感染是一个全球性的公共卫生问题,全球约有2.4亿慢性感染者,目前仍难以治愈。根据病毒学和免疫学特征,CHB自然史通常分为4期:免疫耐受期、免疫清除期、免疫控制期、再活动期。已知有3种抗原系统在HBV感染过程中发挥重要作用,包括HBsAg、HBcAg、HBeAg。理论上,在病毒感染期间,上述3种抗原在特定条件下均能激活B细胞成熟分化,产生相应抗体并形成CIC,这是病毒感染过程中免疫复合物的最主要来源。此外,由于病毒在复制过程中对宿主组织、细胞造成损伤,部分CHB患者血液中可能产生针对HBV其他成分的免疫反应,形成自身免疫复合物,如DNA聚合酶及其抗体、蛋白质和磷脂复合物、甲状腺抗原-抗体复合物等,这些自身免疫反应也可能导致肝损害[14, 27]。

多项研究表明,CHB患者血液循环中的CIC与HBV导致的肝内、肝外损伤及功能性治愈有关。早期研究通过电子显微镜观察到CHB患者血液中以免疫复合物形式存在的表面抗原病毒颗粒[5-6],且其含量与多动脉炎、肾小球肾炎有关[28-29]。针对CHB功能性治愈者的随访研究表明,HBsAg免疫复合物的增多与功能性治愈密切相关[30]。另一方面,CHB患者血液中存在大量衣壳-抗体复合物(capsid-antibody complex,CAC),是HBV RNA的主要载体[31],且针对HBcAg的体液免疫反应异常激活[32],提示CAC在HBV导致的肝脏损伤中起重要作用。然而,CHB患者血液中CIC总量与肝脏炎症、纤维化程度之间的关联,以及其与血清补体水平之间的具体关系仍缺乏完整的研究。

本研究针对CIC检测方法,即固相C1q结合荧光免疫法在CHB患者中的应用,进行了测试与优化,证实其具有良好的线性、特异性和重复性。并采用该方法检测了220例CHB患者以及20例非乙型肝炎的肝炎患者、10例CHB功能性治愈者、20例健康人的血清样本,研究CHB患者血清中的CIC水平及其与病毒学指标、肝功能相关生化指标、肝脏组织学检查结果之间的关系,探索其临床意义。结果显示,CHB患者血清样本中的CIC总量显著高于健康人群,提示其血液中存在更为活跃的体液免疫反应。此外,功能性治愈者血液中的CIC水平显著低于CHB患者,但高于正常人群,提示CHB患者即使获得功能性治愈,其体内仍有潜在的病毒复制或肝脏损伤。

分析CHB患者血清样本中CIC与病毒学指标的关系,结果显示CIC与HBV DNA、HBsAg呈显著正相关,提示CIC的产生与病毒复制活跃程度相关。CIC与肝脏损伤生化指标的相关性分析结果显示,CIC与ALT、AST呈正相关,与Glb显著正相关,与A/G值呈负相关,提示CIC的产生与CHB患者体液免疫的激活和抗体的产生具有一致性,且其质量浓度与肝脏损伤程度相关。

肝脏炎症程度和纤维化程度较高的患者体内,CIC的质量浓度显著高于无显著炎症、无显著纤维化的患者,血清补体C4和C3的水平与肝脏炎症、纤维化程度均呈负相关,CIC水平与补体C4水平呈负相关。不同临床分期的CHB患者中,免疫活动较强(免疫激活期、HBeAg阴性肝炎)的患者体内的CIC水平较高,补体水平较低,而低复制期患者体内的CIC水平较低,补体水平较高。

基于以上结果,本文推测CHB患者血液中存在由CIC清除导致的炎症及补体消耗情况,且CIC的产生与肝脏中的病毒复制情况、免疫活动密切相关。本研究中与CIC呈负相关的补体C4以及C3在病毒激活的补体经典信号通路中发挥着促进CIC吞噬的重要作用[33]。例如,在急性病毒感染所致的肺损伤中,补体可诱导相关趋化因子表达量升高,使炎症细胞聚集[34-35],并导致急性肺损伤,如严重急性呼吸综合征冠状病毒2型(severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,SARS-CoV-2)[36]、甲型流感病毒[37]。在慢性丙型肝炎患者中,有研究认为补体C4对病程进展及复发有重要的监测作用[38]。有文献表明,CHB患者的肝脏中通常存在大量沉积的补体成分C4d[18]。结合本研究结果,推测CHB患者体液免疫被高度激活,可能存在由CIC诱导的补体依赖的细胞毒效应(complement-dependent cytotoxicity,CDC)导致的肝损伤。

目前,研究者们对不同CIC成分在CHB病程进展中的作用仍具有争议。有研究已证实HBcAg及其抗体HBcAb与B细胞在肝内的激活及肝脏损伤密切相关[39-40]。HBcAg能激活更强烈的体液免疫反应,因此其对肝脏的破坏作用更强[7]。HBsAg免疫复合物大量增多被认为是HBsAb产生的证据,是功能性治愈的重要前提。Xu等[30]推测在功能性治愈者中,这种HBsAg免疫复合物的一过性升高往往伴随着HBsAg的大量清除,导致ALT一过性升高。然而,多项研究表明,大部分患者体内针对HBsAg的B细胞功能异常,其产生的抗体缺乏有效诱导HBsAg清除的能力,因此CHB功能性治愈者较为少见[41]。未来可进一步针对CHB患者血液中的CIC成分变化以及T细胞、B细胞、巨噬细胞的活动进行研究,从而能更好地判断不同CIC成分的临床价值。

综上所述,本研究对CIC检测方法,即固相C1q结合荧光免疫法在CHB患者中的应用进行了尝试及优化,并利用该方法证实了CHB患者血液中CIC水平升高,分析了CIC与病毒复制活跃程度、肝脏损伤及补体消耗的相关性,为进一步研究B细胞、补体激活免疫在肝脏损伤及乙型肝炎慢性化中的作用提供了依据。

| [1] |

Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN, Dokmeci AK, Gane E, Hou JL, Jafri W, Jia J, Kim JH, Lai CL, Lee HC, Lim SG, Liu CJ, Locarnini S, Al Mahtab M, Mohamed R, Omata M, Park J, Piratvisuth T, Sharma BC, Sollano J, Wang FS, Wei L, Yuen MF, Zheng SS, Kao JH. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update[J]. Hepatol Int, 2016, 10(1): 1-98.

[DOI]

|

| [2] |

Yancey KB, Lawley TJ. Circulating immune complexes: their immunochemistry, biology, and detection in selected dermatologic and systemic diseases[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1984, 10(5 Pt 1): 711-731.

[DOI]

|

| [3] |

DeWitte M, Haynes J, Freimark B, Martin P, Raymond JT, Evering W, Rebelatto MC, Schenck E, Horvath C. Formation, clearance, deposition, pathogenicity, and identification of biopharmaceutical-related immune complexes: review and case studies[J]. Toxicol Pathol, 2014, 42(4): 725-764.

[DOI]

|

| [4] |

Theofilopoulos AN, Dixon FJ. The biology and detection of immune complexes[J]. Adv Immunol, 1979, 28: 89-220.

[DOI]

|

| [5] |

Shulman NR, Barker LF. Virus-like antigen, antibody, and antigen-antibody complexes in hepatitis measured by complement fixation[J]. Science, 1969, 165(3890): 304-306.

[DOI]

|

| [6] |

Almeida JD, Waterson AP. Immune complexes in hepatitis[J]. Lancet, 1969, 2(7628): 983-986.

[DOI]

|

| [7] |

Farci P, Diaz G, Chen Z, Govindarajan S, Tice A, Agulto L, Pittaluga S, Boon D, Yu C, Engle RE, Haas M, Simon R, Purcell RH, Zamboni F. B cell gene signature with massive intrahepatic production of antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen in hepatitis B virus-associated acute liver failure[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010, 107(19): 8766-8771.

[DOI]

|

| [8] |

Chen Z, Diaz G, Pollicino T, Zhao H, Engle RE, Schuck P, Shen CH, Zamboni F, Long Z, Kabat J, De Battista D, Bock KW, Moore IN, Wollenberg K, Soto C, Govindarajan S, Kwong PD, Kleiner DE, Purcell RH, Farci P. Role of humoral immunity against hepatitis B virus core antigen in the pathogenesis of acute liver failure[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018, 115(48): E11369-E11378.

[DOI]

|

| [9] |

Hart SP, Alexander KM, Dransfield I. Immune complexes bind preferentially to FcγRIIA (CD32) on apoptotic neutrophils, leading to augmented phagocytosis by macrophages and release of proinflammatory cytokines[J]. J Immunol, 2004, 172(3): 1882-1887.

[DOI]

|

| [10] |

Johansson AG, Løvdal T, Magnusson KE, Berg T, Skogh T. Liver cell uptake and degradation of soluble immunoglobulin G immune complexes in vivo and in vitro in rats[J]. Hepatology, 1996, 24(1): 169-175.

[DOI]

|

| [11] |

Cochrane CG. Studies on the localization of circulating antigen-antibody complexes and other macromolecules in vessels: I. Structural studies[J]. J Exp Med, 1963, 118(4): 489-502.

[DOI]

|

| [12] |

Kaul M, Loos M. Dissection of C1q capability of interacting with IgG: time-dependent formation of a tight and only partly reversible association[J]. J Biol Chem, 1997, 272(52): 33234-33244.

[DOI]

|

| [13] |

Vassilopoulos D, Calabrese LH. Management of rheumatic disease with comorbid HBV or HCV infection[J]. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2012, 8(6): 348-357.

[DOI]

|

| [14] |

Maya R, Gershwin ME, Shoenfeld Y. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and autoimmune disease[J]. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2008, 34(1): 85-102.

[DOI]

|

| [15] |

∅ie CI, Wolfson DL, Yasunori T, Dumitriu G, Sørensen KK, McCourt PA, Ahluwalia BS, Smedsrød B. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells contribute to the uptake and degradation of entero bacterial viruses[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 898.

[DOI]

|

| [16] |

Yuan F, Zhang W, Mu D, Gong J. Kupffer cells in immune activation and tolerance toward HBV/HCV infection[J]. Adv Clin Exp Med, 2017, 26(4): 739-745.

[DOI]

|

| [17] |

Pham BN, Mosnier JF, Durand F, Scoazec JY, Chazouilleres O, Degos F, Belghiti J, Degott C, Benhamou JP, Erlinger S, Cohen JHM, Bernuau J. Immunostaining for membrane attack complex of complement is related to cell necrosis in fulminant and acute hepatitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 1995, 108(2): 495-504.

[DOI]

|

| [18] |

Bouron-Dal Soglio D, Rougemont AL, Herzog D, Soucy G, Alvarez F, Fournet JC. An immunohistochemical evaluation of C4d deposition in pediatric inflammatory liver diseases[J]. Hum Pathol, 2008, 39(7): 1103-1110.

[DOI]

|

| [19] |

Kosmidis JC, Leader-Williams LK. Complement levels in acute infectious hepatitis and serum hepatitis[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 1972, 11(1): 31-35.

[PubMed]

|

| [20] |

Truedsson L, Bengtsson AA, Sturfelt G. Complement deficiencies and systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Autoimmunity, 2007, 40(8): 560-566.

[DOI]

|

| [21] |

Theofilopoulos AN, Wilson CB, Dixon FJ. The Raji cell radioimmune assay for detecting immune complexes in human sera[J]. J Clin Invest, 1976, 57(1): 169-182.

[DOI]

|

| [22] |

Madalinski K, Burczynska B, Heermann KH, Uy A, Gerlich WH. Analysis of viral proteins in circulating immune complexes from chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 1991, 84(3): 493-500.

[PubMed]

|

| [23] |

Agnello V, Winchester RJ, Kunkel HG. Precipitin reactions of the C1q component of complement with aggregated γ-globulin and immune complexes in gel diffusion[J]. Immunology, 1970, 19(6): 909-919.

[DOI]

|

| [24] |

Zubler RH, Lange G, Lambert PH, Miescher PA. Detection of immune complexes in unheated sera by a modified 125I-C1q binding test. Effect of heating on the binding of C1q by immune complexes and application of the test to systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. J Immunol, 1976, 116(1): 232-235.

[DOI]

|

| [25] |

Collins MM, Casavant CH, Stites DP. Solid-phase Clq-binding fluorescence immunoassay for detection of circulating immune complexes[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1982, 15(3): 456-464.

[DOI]

|

| [26] |

Kouser L, Madhukaran SP, Shastri A, Saraon A, Ferluga J, Al-Mozaini M, Kishore U. Emerging and novel functions of complement protein C1q[J]. Front Immunol, 2015, 6: 317.

[DOI]

|

| [27] |

von Herrath MG, Oldstone MB. Virus-induced autoimmune disease[J]. Curr Opin Immunol, 1996, 8(6): 878-885.

[DOI]

|

| [28] |

Trepo CG, Zucherman AJ, Bird RC, Prince AM. The role of circulating hepatitis B antigen/antibody immune complexes in the pathogenesis of vascular and hepatic manifestations in polyarteritis nodosa[J]. J Clin Pathol, 1974, 27(11): 863-868.

[DOI]

|

| [29] |

Combes B, Shorey J, Barrera A, Stastny P, Eigenbrodt EH, Hull AR, Carter NW. Glomerulonephritis with deposition of Australia antigen-antibody complexes in glomerular basement membrane[J]. Lancet, 1971, 2(7718): 234-237.

[DOI]

|

| [30] |

Xu H, Locarnini S, Wong D, Hammond R, Colledge D, Soppe S, Huynh T, Shaw T, Thompson AJ, Revill PA, Hogarth PM, Wines BD, Walsh R, Warner N. Role of anti-HBs in functional cure of HBeAg+ chronic hepatitis B patients infected with HBV genotype A[J]. J Hepatol, 2022, 76(1): 34-45.

[DOI]

|

| [31] |

Bai L, Zhang X, Kozlowski M, Li W, Wu M, Liu J, Chen L, Zhang J, Huang Y, Yuan Z. Extracellular hepatitis B virus RNAs are heterogeneous in length and circulate as capsid-antibody complexes in addition to virions in chronic hepatitis B patients[J]. J Virol, 2018, 92(24): e00798-18.

[DOI]

|

| [32] |

Le Bert N, Salimzadeh L, Gill US, Dutertre CA, Facchetti F, Tan A, Hung M, Novikov N, Lampertico P, Fletcher SP, Kennedy PTF, Bertoletti A. Comparative characterization of B cells specific for HBV nucleocapsid and envelope proteins in patients with chronic hepatitis B[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 72(1): 34-44.

[DOI]

|

| [33] |

Stoermer KA, Morrison TE. Complement and viral pathogenesis[J]. Virology, 2011, 411(2): 362-373.

[DOI]

|

| [34] |

Wang R, Xiao H, Guo R, Li Y, Shen B. The role of C5a in acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic viral infections[J]. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2015, 4(5): e28.

[DOI]

|

| [35] |

Bosmann M, Ward PA. Role of C3, C5 and anaphylatoxin receptors in acute lung injury and in sepsis[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2012, 946: 147-159.

[DOI]

|

| [36] |

Lo MW, Kemper C, Woodruff TM. COVID-19: complement, coagulation, and collateral damage[J]. J Immunol, 2020, 205(6): 1488-1495.

[DOI]

|

| [37] |

Garcia CC, Weston-Davies W, Russo RC, Tavares LP, Rachid MA, Alves-Filho JC, Machado AV, Ryffel B, Nunn MA, Teixeira MM. Complement C5 activation during influenza A infection in mice contributes to neutrophil recruitment and lung injury[J]. PloS One, 2013, 8(5): e64443.

[DOI]

|

| [38] |

Dumestre-Perard C, Ponard D, Drouet C, Leroy V, Zarski JP, Dutertre N, Colomb MG. Complement C4 monitoring in the follow-up of chronic hepatitis C treatment[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2002, 127(1): 131-136.

[DOI]

|

| [39] |

Vanwolleghem T, Groothuismink ZMA, Kreefft K, Hung M, Novikov N, Boonstra A. Hepatitis B core-specific memory B cell responses associate with clinical parameters in patients with chronic HBV[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(1): 52-61.

[DOI]

|

| [40] |

Zgair AK, Ghafil JA, Al-Sayidi RH. Direct role of antibody-secreting B cells in the severity of chronic hepatitis B[J]. J Med Virol, 2015, 87(3): 407-416.

[DOI]

|

| [41] |

Burton AR, Pallett LJ, McCoy LE, Suveizdyte K, Amin OE, Swadling L, Alberts E, Davidson BR, Kennedy PT, Gill US, Mauri C, Blair PA, Pelletier N, Maini MK. Circulating and intrahepatic antiviral B cells are defective in hepatitis B[J]. J Clin Invest, 2018, 128(10): 4588-4603.

[DOI]

|

2022, Vol. 17

2022, Vol. 17