2. 南京医科大学基础医学院,江苏 南京 211100

2. Basic Medical Sciences, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211100, Jiangsu Province, China

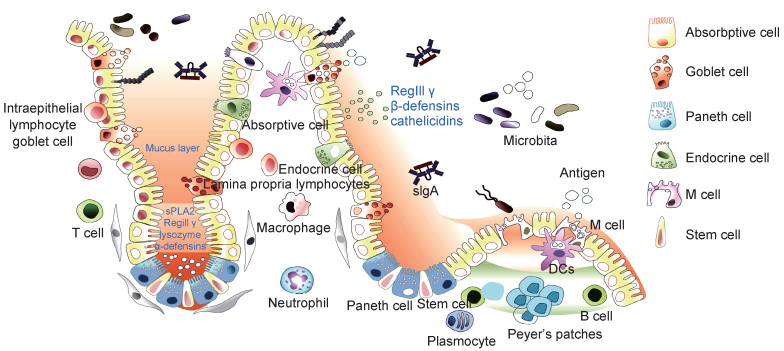

肠道是机体主要消化器官,也是机体重要免疫器官,处于机体免疫防御的最前线。肠黏膜是机体与病原发生相互作用的主要场所,肠道中有大量肠道菌群定植,它们与宿主共生,在肠道免疫中发挥重要作用[1]。根据目前研究结果,肠道免疫系统主要由肠道菌群、肠道上皮细胞(intestinal epithelial cell,IEC)、肠上皮内淋巴细胞(intraepithelial lymphocyte,IEL)、固有层淋巴细胞(lamina propria lymphocyte,LPL)及派氏淋巴结(Peyer’s patch,PP)等构成(图 1)。

|

| In small intestine, there are various different types of cells localized in the gut epithelium along the crypt-villus axis, in which each type of epithelial cells plays unique role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Enterocytes, the most prominent cell type of the intestinal epithelium, are responsible for nutrient and water absorption and also produce antimicrobial peptides such as RegIII γ, β-defensins, cathelicidins to defend against invading pathogens. Paneth cells located at the bottom of the crypt produce amounts of specific antimicrobial peptides (lysozyme, α-defensins, sPLA2). M cells are localized in the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) overlying Peyer's patches and can directly participate in antigen uptake and passage to underlying immune cells. Goblet cells secret mucin and promote luminal antigens transfer to dendritic cells. Endocrine cells are stimulated by antigens to produce transmitters, which contribute to the digestive function of intestine system and regulate intestinal immune function. In addition, there are a large number of immune cells distributed in the intestinal epithelium and lamina propria of the intestine, such as macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, monocytes, lymphocytes and plasma cells, etc, which form a complex network to monitor the intestinal immune microenvironment as the first line of host defense against threats from the microbiome. Moreover, plenty of microbiota in intestine are not only the threat to host, but also play key roles as one of the components of intestinal mucosal immune system. Intestinal microbiota can competitively inhibit the colonization of pathogenic bacteria in the intestine, stimulate the development of the intestinal mucosal immune system, and regulate intestinal epithelial function by secreting metabolites. 图 1 肠道免疫系统主要构成 Fig. 1 The components of intestinal mucosal immune system |

肠道微生物群是人类胃肠道中发现的微生物或有机体的集合,包括细菌、古菌、真菌、原生动物和病毒[2]。肠道菌群有数万亿个共生微生物,主要包括5个细菌门:厚壁菌门、拟杆菌门、放线菌门、变形杆菌门和梭状菌门,其中拟杆菌和厚壁菌占肠道总菌群的90%左右(分别占25%和65%)。肠道菌群在不同肠段中定植的种类存在差异,小肠中梭状菌、链球菌和乳酸杆菌等为优势菌群,而盲肠、结肠和直肠中的优势菌群是厚壁菌和拟杆菌[1]。肠道微生物群不仅对机体吸收营养物质至关重要,还有助于抵御其他病原菌入侵,并为免疫系统正常发育提供必需的条件[3]。有研究比较了菌群移植前后实验动物消化道的状态,发现无菌动物胃肠道蠕动减慢,小肠绒毛增长,肠壁变薄,相关淋巴组织不发达,上皮淋巴细胞、黏膜中IgA+浆细胞和CD4+ T细胞减少,抗原呈递细胞的主要组织相容性复合物(major histocompatibility complex,MHC)Ⅱ分子表达下降。重新移植菌群后,肠道收缩加快,绒毛变短,血管增生,淋巴细胞聚集到黏膜,淋巴细胞对抗原的反应速度和强度均增加,肠道免疫功能显著增强[4]。有研究报道,肠道菌群可分泌信号分子,促进黏膜免疫系统中免疫细胞数量增加和分化,并诱导黏液及抗菌肽等分子表达[5]。肠道微生物的显著变化会调控天然免疫和适应性免疫细胞的发育[6],进而影响肠道内稳态及机体免疫系统功能。已有大量研究表明,菌群失调与许多疾病的发生密切相关,如肥胖、糖尿病、心脑血管疾病、炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease,IBD)、肠易激惹综合征(irritable bowel syndrome,IBS)、自身免疫病、过敏、自闭症、抑郁症及老年性痴呆等。肠道菌群失调可增加肠道中游离氨基酸,特别是脯氨酸,艰难梭菌(Clostridium difficile)可利用这些氨基酸作为能量来源,促进艰难梭菌感染,造成严重腹泻,甚至引起死亡[7]。肠道菌群紊乱导致物质代谢异常,可引发心血管疾病。膳食胆碱、磷脂酰胆碱或甜菜碱依赖肠道菌群的代谢产物——氧化三甲胺(trimetlylamine oxide,TMAO),能增加心血管疾病的患病风险。主要来源于鸡蛋、牛奶、肝脏、红色肉类、鱼类等的磷脂酰胆碱,在肠道中首先被肠道菌群代谢生成三甲胺,三甲胺在肝脏黄素单加氧酶的作用下形成TMAO,进而通过调节巨噬细胞表面清道夫受体的表达水平,参与动脉粥样硬化过程[8]。因此,肠道菌群不仅调节肠道黏膜免疫,对机体其他系统功能的有效发挥也有重要帮助。

1.2 肠道上皮细胞肠道上皮细胞是参与肠道黏膜免疫的主要功能细胞,主要包括吸收性柱状上皮细胞、杯状细胞、潘氏细胞、内分泌细胞、M细胞等。它们呈单层紧密排列,组成肠道上皮组织并覆盖于黏膜表面,除能消化吸收肠道营养及形成黏膜物理屏障阻碍细菌入侵外,还参与浆细胞分泌的IgA抗体转运、抗原呈递、细胞因子分泌等免疫活动。肠道上皮细胞中肠细胞占80%以上,其表面的微绒毛结构增大了与外界物质接触的表面积,同时刷状缘表面表达分泌多种蛋白质降解酶,可对肠腔中的蛋白质等进行充分降解和吸收[9]。肠细胞之间形成紧密连接,构成肠道黏膜的主要物理屏障,且在肠道细菌刺激下,肠细胞可分泌大量抗菌物质如RegⅢ γ、β -defensin、抗菌肽等,直接杀灭细菌进而控制肠道菌群稳态[10]。杯状细胞是维持上皮细胞屏障功能的一群特化细胞,在肠道黏膜免疫中有重要功能。杯状细胞可分泌多种黏液蛋白,组成肠道上皮组织黏液屏障,通过疏水作用结合肠道细菌抗原蛋白,进而限制其侵入肠黏膜[11]。潘氏细胞位于肠道隐窝底部,主要功能是分泌抗菌分子杀灭入侵细菌;此外,潘氏细胞紧邻肠道干细胞,可分泌WNT信号分子和乳酸代谢分子等,对肠道干细胞增殖和分化有重要调节作用。因此,潘氏细胞对肠道发育和肠道黏膜防御至关重要[10]。肠道上皮还存在内分泌细胞,这些细胞在抗原刺激下会释放小分子递质(如5-羟色胺、组胺、促胰液素、胆囊收缩素-促胰酶素),刺激肠道神经和免疫细胞发挥功能,可帮助肠道蠕动,促进肠道消化吸收营养物质,还可调节肠道黏膜免疫防御[5]。M细胞是一种存在于肠道上皮组织中特化的抗原转运细胞,其细胞表面无微绒毛结构,不分泌消化酶和黏液,因此抗原物质更容易通过M细胞进入肠黏膜派氏淋巴结中,被树突细胞摄取、加工并呈递给T细胞,进而激活免疫应答和促进浆细胞分泌IgA抗体来防御入侵肠道细菌[12]。此外,大量研究表明,肠道上皮细胞在肠道细菌刺激下会产生大量免疫效应分子,如炎症和趋化因子——白细胞介素18(interleukin 18,IL-18)、IL-6、肿瘤坏死因子α (tumor necrosis factor α,TNF-α)、人单核细胞趋化蛋白1(monocyte chemotactic protein 1,MCP-1)等,对肠道免疫细胞的招募、增殖、活化和免疫应答发生具有重要作用[4]。由此可见,肠道上皮细胞既能促进机体对食物营养物质的吸收,也能形成物理屏障阻碍肠道细菌侵入肠黏膜,还能作为连接天然免疫与适应性免疫应答的桥梁,其多元化角色对维持肠道微环境稳态平衡至关重要[13]。

1.3 肠道免疫细胞肠上皮内淋巴细胞和固有层淋巴细胞是肠道主要免疫细胞。肠上皮内淋巴细胞是机体内最大的淋巴细胞群,约90%是CD3+ T细胞,其中一半为CD3+ CD8+ T细胞,可通过Fas受体诱导细胞凋亡来清除入侵病原,并分泌细胞因子调节肠道上皮细胞和固有层淋巴细胞功能,目前对其功能的研究还在探索中[14]。固有层白细胞主要包括树突细胞、分泌IgA的浆细胞、T细胞和固有淋巴样细胞(innate lymphoid cell,ILC)等[13]。

树突细胞是专职抗原呈递细胞之一。小鼠肠道中的树突细胞亚群高表达CD11c和MHCⅡ分子,但不表达IgG高亲和力受体CD64[15]。定居在肠道固有层的树突细胞为CD103-CX3CR1+亚群,其树突能在肠道上皮细胞间隙延伸至肠腔摄取抗原,主要发挥抗原加工和呈递功能。另一种树突细胞为CD103+CX3CR1-亚群,可进一步分为CD11b+CD8α-和CD11b-CD8α+两种小亚群[16]。有研究发现,CD103+CD11b+和CD103+CD8α+亚群可迁移至派氏淋巴结和肠系膜淋巴结(mesenteric lymph node,mLN)中,促进初始T细胞分化、成熟和免疫耐受形成,在肠道黏膜免疫中发挥重要作用[16]。

肠道固有层存在大量B细胞,细胞膜表面主要表达分泌型IgA。虽然IgM是B细胞首先产生的免疫球蛋白,但B细胞在淋巴组织生发中心受到抗原刺激和滤泡辅助T细胞(follicular helper T,Tfh)作用,会发生抗体类别转换(class-switch recombination,CSR),产生IgG、IgA和IgE。在肠道特定的免疫微环境中,如转化生长因子β (transforming factor β,TGF- β)及IL-10等细胞因子大量存在,促进B细胞分化为分泌型IgA浆细胞,其分泌的IgA通过肠道上皮细胞转运进入肠腔,通过抗体中和作用来控制肠道细菌侵入。因此,IgA分泌型B细胞对肠道菌群调节和肠道黏膜免疫防御有极为重要的作用[14]。

肠道T细胞广泛分布于派氏淋巴结、肠系膜淋巴结、固有层及肠道上皮组织内。T细胞根据其表面受体的不同分为γδ T细胞与αβ T细胞,在肠道免疫中均有重要作用。有研究发现,大肠埃希菌可激活γδ T细胞产生细胞因子γ干扰素(interferon γ,IFN-γ),IFN-γ进一步刺激巨噬细胞释放IL-15,促进γδ T细胞在感染部位聚集和激活,进而诱发抗感染免疫[17]。此外,γδ T细胞激活可释放炎症因子IL-17,IL-17在肠道免疫中有重要作用,可招募中性粒细胞抵抗肠道细菌感染[18]。αβ T细胞对抗原识别具有特异性,在肠道树突细胞作用下,初始T细胞(naïve T cell,Tn)可激活分化成不同T细胞亚群,主要包括Th1、Th2、Th17、调节性T细胞(regulatory T,Treg)和CD8+NKT细胞等,这些T细胞在肠道黏膜免疫防御中均有重要功能。Th1细胞可分泌IFN-γ和TNF-α等炎症因子来促进抗感染,从而抵御肠道细菌侵入[19]。Th2细胞主要分泌IL-4、IL-5、IL-10等免疫效应分子,可诱导IgA型B细胞产生,进而释放大量IgA以保护肠道黏膜[20]。Th17细胞可释放IL-17、IL-22、IL-21、粒细胞-巨噬细胞集落刺激因子(granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor,GM-CSF)等多种炎症因子,不仅可招募中性粒细胞和单核巨噬细胞清除肠道细菌感染,还可促进肠道上皮细胞分泌抗菌肽直接杀灭细菌,并促进肠道上皮细胞的损伤修复[21]。Treg细胞具有免疫抑制作用,通常可抑制效应T细胞的过度增殖和活化,进而减轻过强免疫炎症反应带来的免疫病理损伤[22]。在肠道固有层中,Treg细胞主要通过产生IL-10、TGF- β等细胞因子来负调控效应T细胞的过度激活。因此,Treg细胞对维持肠道内稳态和抑制肠道炎症的发生具有重要作用[23]。CD8+ NKT细胞也参与肠道黏膜免疫反应。有研究发现,口服假结核耶尔森菌后可诱导CD8+ T细胞在固有层聚集,进而控制肠道局部感染进程[24]。健康人肠道中的T细胞在肠道黏膜免疫和肠道内稳态维持过程中发挥着积极作用,然而IBD患者体内由于肠道免疫功能紊乱,T细胞常处于过度激活状态。有研究表明,克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease)和溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis)患者肠道和外周血中T细胞显著增多,且患者炎症部位T细胞呈现Th17和Th1细胞共有特征,可同时分泌IL-17和IFN-γ炎症因子[25],因此针对T细胞的治疗方法将是临床肠炎研究的重要方向。

ILC是近年来发现的一类重要的天然免疫细胞亚群,具有天然免疫和获得性免疫细胞双重特征。其与天然免疫细胞类似,可被病原迅速激活,但产生的效应分子与Th细胞相同。根据其分泌的细胞因子可分为4类,即ILC1、ILC2、ILC3和ILCreg细胞,与T细胞中的Th1、Th2、Th17及Treg相对应,在肠道黏膜免疫中发挥重要作用[26]。ILC1细胞在小肠和结肠中均有分布,产生IFN-γ、TNF-α等细胞因子,激活肠道抗感染反应[27]。ILC2细胞主要分泌IL-5、IL-13,在肠道抗寄生虫反应中有重要作用[28]。ILC3细胞产生IL-17和IL-22,可保护肠道上皮,抵抗感染发生[29]。ILCreg是新近鉴别的可分泌IL-10抑炎性细胞因子的ILC,可调节肠道稳态,抑制肠道炎症发生[14]。ILC在肠道细菌刺激后会产生大量细胞因子,如TNF-α、IFN-γ、IL-17等,进而激发免疫炎症以清除病原体,但肠道中的ILC过度活化也会导致肠道炎症,引起炎性肠道疾病发生[30]。

2 炎症小体与肠道黏膜免疫肠道免疫的诱导物包括食物和肠道微生物中的刺激分子和病原蛋白。天然免疫反应是机体阻碍病原入侵、清除有害物质、维持肠道免疫稳态的重要防御机制。作为病原感受器,分布于肠道上皮细胞的天然免疫模式识别受体(pattern-recognition receptor,PRR)如Toll样受体(Toll-like receptor,TLR)、Nod样受体(NOD-like receptor,NLR)、RIG-Ⅰ样受体(RIG-Ⅰ-like receptor,RLR)等中,可识别病原相关分子模式(pathogen-associated molecular pattern,PAMP)配体,激活下游信号通路和分子事件,诱导抗感染细胞因子及其他肠道黏膜免疫防御分子的表达,促进黏膜免疫反应发生[31]。目前,已发现多个IBD致病或易感基因为天然免疫分子,如NOD2、ATG16L、TLR9、NLRP3等[32]。研究表明,PRR在机体其他组织区域中的免疫作用多集中在促炎症效应,在肠道中则不同,分布于肠道上皮细胞的PRR不仅可诱导炎症招募免疫细胞,还可诱导上皮细胞释放抗菌分子并直接引起上皮细胞死亡来清除入侵病原,因此肠道上皮细胞PRR对防御肠道菌群入侵和维持肠道内环境稳定具有独特而强大的作用。炎症小体是一类重要的NLR类PRR,是多蛋白组成的大分子复合体,其功能异常与许多感染和免疫疾病发生有关[33]。近年来研究表明,IBD、IBS等肠道免疫相关疾病与炎症小体的非正常活化有密切关系,炎症小体在肠道黏膜免疫中的作用越来越受到重视。

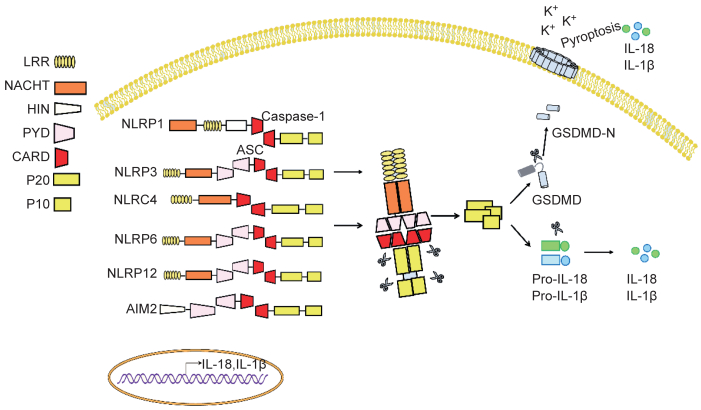

2.1 炎症小体炎症小体也称炎性小体,为一种多蛋白复合体,是天然免疫系统的重要组成。根据核心分子不同,主要分为NLR和AIM2样受体(AIM2-like receptor,ALR)家族[11]。目前研究较多的炎症小体主要包括NLRP3、NLRP1、NLRC4、NLRP6、NLRP12和AIM2(图 2)。炎症小体能识别外源性的PAMP或内源性的危险相关分子模式(danger-associated molecular pattern,DAMP)[34],参与病原感染免疫防御及细胞损伤和代谢异常等导致的炎症反应。炎症小体激活后可促进蛋白酶Caspase-1和Caspase-11(人为Caspase-4/5)的激活,激活的Caspase可诱导IL-1和IL-18前体剪切而成熟。大量研究表明,炎症小体激活产生的IL-1 β和IL-18具有广泛的生物学功能,在免疫和炎症反应中起重要作用。其中IL-1是一种多功能细胞因子,在局部可诱导IL-6、IL-8、CCL2等细胞因子表达,帮助中性粒细胞及单核细胞迁移至感染和损伤部位,激活炎症反应[14]。此外,IL-1也可促进树突细胞、巨噬细胞和中性粒细胞的活化[35],且在免疫应答反应中增强T细胞的激活[4],与其他细胞因子协同作用可促进Th17细胞形成[36]。IL-1在肠道炎症中的作用已被许多研究报道,阻断IL-1可改善梭状芽胞杆菌相关性结肠炎和沙门菌诱导的肠炎,提示IL-1在IBD中是一种促炎细胞因子,发挥炎症损伤病理作用[37]。炎症小体下游的另一效应因子IL-18不仅可激活单核细胞[26],还能诱导T细胞产生IFN-γ,被认为是一种促Th1分化细胞因子[28]。在一定条件下,IL-18也可激活γδ T细胞驱动IL-17产生[38]。在肠道未发生感染和炎症稳态的情况下,肠道上皮细胞是IL-18的主要来源[39],其释放的IL-18被认为具有促进肠上皮修复、增殖和成熟的功能[29]。最近研究发现,Caspase激活还可切割Gasdermin D蛋白(GSDMD),引起炎性死亡或细胞焦亡(pyroptosis)发生,这种新鉴定出的细胞死亡方式是一种“炎性细胞程序化死亡”。GSDMD被蛋白酶Caspase切割后,其N端结构域片段释放并寡聚化,随后结合到细胞膜上形成10~15 nm的孔洞,进一步促进成熟IL-1 β和IL-18释放,激活炎症反应[40]。此外,GSDMD蛋白的N端片段寡聚化形成的孔洞会引起细胞渗透压失衡和细胞膨胀,导致炎性死亡或细胞焦亡发生[32]。已有研究表明,细胞焦亡可破坏病原感染的细胞,抑制病原在细胞内的复制,并促进IL-1 β和IL-18释放,激活炎症反应,引起针对相关病原的免疫应答发生,进而刺激机体免疫系统对病原感染的清除[20]。虽然细胞焦亡可保护机体免受病原感染的侵袭,但如果过度激活,会导致致命的脓毒症发生[41]。有研究显示,GSDMD缺失会削弱机体对肠道细菌和肠道病毒的清除[42],但其在肠道免疫中的具体角色仍需深入研究。

|

| Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes, mainly including NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, NLRP6, and NLRP12, as well as AIM2 identified so far. The major components of inflammasomes consist of core proteins, adaptor proteins, caspase and some regulatory proteins. The core protein usually contains leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains, nucleotide-binding and oligomerization (NACHT) domains, a protease caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) or pyrin domain (PYD). However, the core protein of AIM2 inflammasome has a HIN-200 domain in its C-terminus that can bind to DNA. After sensing signal stimulation, inflammasome will assemble and recruit the protease caspase-1 and caspase-11 through CARD domain, then subsequently auto-activate caspase to form P20/P10 protease complex. The activated caspase not only converts pro-IL-18, pro-IL-1 β to mature form, but also cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD) to induce pyroptosis, thus promoting inflammation. Additionally, some inflammasomes such as NLRP3, NLRP6, NLRP12 contain PYD domain instead of CARD domain to recruit apoptosis-associated speck-like proteins (ASCs), followed by recruitment of caspase through CARD domain of ASC. 图 2 炎症小体 Fig. 2 Inflammasomes |

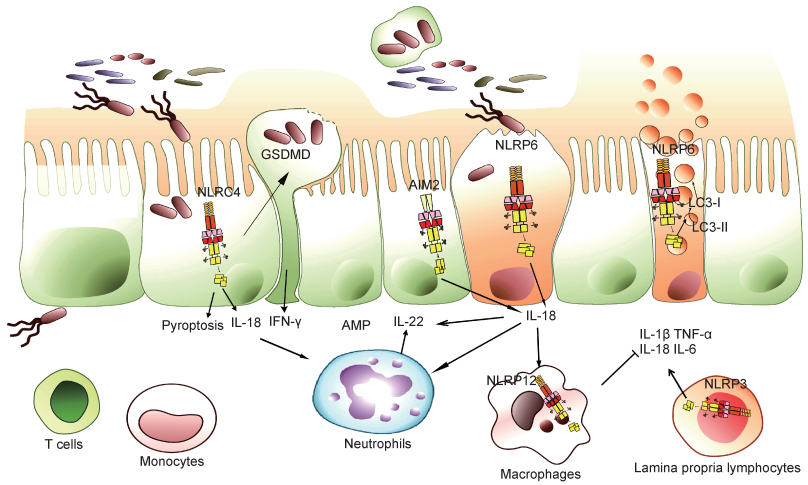

NLRP3是炎症小体家族中的最主要一员,可被细菌毒素、ATP、线粒体活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)及尿素结晶等多种病原和体内危险信号分子激活,是抗感染免疫和炎症性疾病发生过程中的重要角色[43]。在未发生感染和炎症稳态的情况下,肠道中NLRP3的表达水平较低,一旦激活后会在肠道免疫细胞中上调表达,随后组装激活蛋白酶Caspase-1,促进IL-1 β和IL-18前体的切割成熟,引发炎症反应[11]。临床流行病学研究发现,人染色体1q44下游NLRP3的单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP)突变与克罗恩病发生相关[44]。在瑞典进行的一项研究分析了482例克罗恩病患者的SNP位点,发现CARD8和NALP3位点突变与克罗恩病发病的相关性最大,且有偏好男性的倾向[45]。除与肠道炎症病理作用相关外,NLRP3在生理状态下可保护肠道免受病原体侵害,其诱导的炎症反应可激活免疫应答,控制肠道细菌感染[46]。NLRP3炎症小体不仅参与IBD的发生,还有研究发现其异常激活与肠道肿瘤的形成密切相关[47]。已知动物脂肪的饱和脂肪酸可作为NLRP3炎症小体激活反应的刺激物,引起内质网应激反应[48],而大豆蛋白等可抑制NLRP3炎症小体异常激活[49](图 3)。

|

| Upon pathogen invading into the epithelial cells, inflammasomes in the epithelium, such as NLRP6, NLRC4 and AIM2, will be activated to secret cytokine IL-18, which subsequently stimulates intestinal epithelial or immune cells to produce IL-22. IL-22 acts on intestinal epithelial cells to induce the production of antimicrobial peptides and proteins required for the intestinal epithelial repair. Activation of inflammasomes in epithelial cells can also cause pyroptosis, which is activated and assembled by GSDMD protein to form membrane pores, leading to cell swelling and death. Pyroptosis can release the invading bacteria of epithelial cells and stimulate immune response to enhance mucosal immune defense. NLRP6 inflammasome in goblet cells not only promotes IL-18 secretion and pyroptosis, but also facilitates mucin protein secretion by regulating autophagy to protect intestinal epithelial integrity. NLRP12 inflammasome mainly perturbs immune signaling pathways of immune cells and inhibits excessive inflammatory responses. NLRP3 inflammasome plays roles in the immune cells of lamina propria, which can activate the inflammatory response and promote mucosal immune defense in the homeostatic state, but cause inflammatory pathological damage in the excessive infection state. 图 3 炎症小体和肠道黏膜免疫 Fig. 3 Inflammasomes and intestinal mucosal immunity |

NLRC4炎症小体可被致病性革兰阴性沙门菌的细胞内鞭毛蛋白和Ⅲ型分泌系统(type Ⅲ secretion system,T3SS)组分激活[50]。NLRC4炎症小体激活后,会促进IL-1 β和IL-18前体的成熟分泌,并引起细胞焦亡的发生[50]。NLRC4炎症小体在维持肠道稳态平衡方面发挥着重要作用。肠道上皮细胞中的NLRC4炎症小体激活可引起上皮细胞焦亡,导致细菌感染的细胞脱落,阻碍肠道细菌对肠道黏膜的侵袭,还可促进上皮细胞分泌IL-18,对肠道黏膜完整性有重要保护作用[51]。然而,NLRC4炎症小体过度激活也可能导致严重的上皮破坏和病理损伤[52]。此外,NLRC4炎症小体还参与p53下游凋亡通路[53],但其在肠道肿瘤发生中的作用还需进一步探索(图 3)。

2.4 NLRP6炎症小体与肠道NLRP6最初被称为PYPAF5,在肾、肝、肺、大肠和小肠中高表达。肠道中NLRP6主要表达于肠道上皮细胞,如杯状细胞,其对肠道黏膜自我更新修复和黏液蛋白分泌至关重要[54]。近年来研究表明,NLRP6通过多种机制参与调控宿主对病原的防御和肠道内稳态,包括炎症小体效应、免疫信号通路激活、自噬作用等[55]。NLRP6能通过下游效应分子IL-18促进上皮细胞修复和分泌抗菌肽,且能通过自噬促进肠上皮黏液层形成[55]。NLRP6还可防御肠道病毒感染,相关研究表明肠道中NLRP6可作为病毒传感器来调节肠道抗病毒反应[56]。由于NLRP6在肠道中作用重要,其表达受多种因素调节,如肠道菌群可调节NLRP6表达[57],水缺乏引起的应激效应也可通过促肾上腺皮质激素释放来抑制NLRP6表达[58]。对NLRP6活性调控因子的研究发现,胆汁酸衍生物牛磺酸可作为NLRP6信号通路的正调控因子,而精胺和组胺可作为负调控因子[57]。目前,关于NLRP6在人类胃肠道疾病中的作用数据很少,亟待进一步探索与研究(图 3)。

2.5 NLRP12炎症小体与肠道NLRP12炎症小体功能异常与IBD发生有密切关系,但其对肠道黏膜免疫的调节作用复杂,涉及宿主基因组、微生物菌群和炎症反应的动态交互作用。通过比较同卵双胞胎和其他患者,发现NLRP12在人类溃疡性结肠炎中表达较低。小鼠研究发现,NLRP12缺乏会引起结肠炎症增加,并导致菌群多样性发生改变,如肠道益生菌Lachnospiraceae减少,结肠炎相关的Erysipelotrichaceae显著增加[59]。NLRP12缺陷引起的菌群失衡及结肠炎症状可被炎性因子抗体治疗或益生菌Lachnospiraceae干预治疗所逆转[59]。将无特定病原体(specific pathogen free,SPF)级小鼠粪便移植到无菌NLRP12缺陷小鼠中,可引起后者异常免疫信号的抑制和结肠炎症状的逆转,与此同时对NLRP12缺陷小鼠中炎症因子进行阻断可逆转菌群的失调[59]。这些研究结果表明,NLRP12在肠道中对肠道菌群和黏膜免疫系统有双重调节作用,为认识、研究和治疗IBD提供了新的思路(图 3)。

2.6 AIM2炎症小体与肠道AIM2是干扰素诱导基因HIN-200家族的成员之一,是一种胞质DNA感受器[60]。AIM2炎症小体在肠道多种细胞中表达,包括巨噬细胞、淋巴细胞、上皮细胞等。相关研究表明,肠道微生物DNA可激活AIM2炎症小体,后者的激活进一步诱导IL-1 β和IL-18产生。AIM2炎症小体产生的IL-18与上皮细胞或免疫细胞的IL-18受体结合,诱导抗菌肽分子表达,因此其可通过抗菌肽调节肠道微生态,对维持肠道稳态及抵御病原体入侵起关键作用[61]。AIM2还与辐射引起的肠炎有关,缺乏AIM2的小鼠由于蛋白酶Caspase介导的肠道上皮细胞焦亡作用削弱而减轻了辐射诱导的肠道损伤[61]。AIM2也参与结直肠癌的发生,AIM2基因突变在遗传性非息肉病性结直肠癌患者中已被发现[62]。小鼠研究表明,非造血细胞来源的AIM2通过不同于其炎症小体的调控机制(如抑制过度AKT激活和WNT信号异常),调节肠道干细胞不受控制的增殖,防止肠道肿瘤发生[63]。综上,AIM2也许可作为干预肠道疾病的治疗靶点,但相关临床研究还需深入[64](图 3)。

2.7 Gasdermin家族与肠道Gasdermin是一类保守蛋白家族,包括GSDMA、GSDMB、GSDMC、GSDMD、GSDME和DFNB59,大多数已被证明具有成孔活性[65],主要在免疫细胞中表达[66]。近年来研究较多的是GSDMD,它可通过“经典”和“非经典”途径激活,导致细胞焦亡[40],已被确定为蛋白酶Caspase-1和Caspase-11(人为蛋白酶Caspase-4/5)的直接下游靶点[65]。GSDMD被裂解后其N端释放并寡聚结合到胞膜上,形成细胞焦亡过程中质膜上的功能性孔隙,引起膜的肿胀和破裂[67],还与释放IL-1 β和IL-18有关[67]。GSDMD如果过度激活,会导致致命的脓毒症发生。有研究表明,GSDMD可插入富含心磷脂的细菌膜中,发挥杀菌作用[40]。其在肠道黏膜免疫中也可能发挥重要作用,参与细菌感染的上皮细胞的脱落[51]及对肠道病毒的清除[68],但具体作用仍需深入研究。此外,有研究发现GSDMA、GSDMC、GSDMD在消化道肿瘤样本中均沉默表达,很可能在消化道肿瘤发生过程中扮演了重要角色[69](图 3)。

3 结语在宿主与微生物共同进化的漫漫时间长河里,肠道免疫系统进化出复杂但有效的策略来应对外界病原的挑战。最近大量研究表明,炎症小体在肠道免疫中的作用至关重要,但作用机制远未阐明。近年来,Gasdermin家族的发现为炎症小体的肠道免疫研究提供了新的方向和线索,但仍需进一步探索。肠道黏膜免疫研究方兴未艾,深入研究肠道免疫系统的作用机制对攻克相关疾病、造福人类健康具有重大意义。

| [1] |

Rajili Ac' -Stojanovi Ac' M, Smidt H, de Vos WM. Diversity of the human gastrointestinal tract microbiota revisited[J]. Environ Microbiol, 2007, 9(9): 2125-2136.

[DOI]

|

| [2] |

Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism[J]. Nature, 2012, 489(7415): 242-249.

[DOI]

|

| [3] |

Kosiewicz MM, Zirnheld AL, Alard P. Gut microbiota, immunity, and disease: a complex relationship[J]. Front Microbiol, 2011, 2: 180.

[DOI]

|

| [4] |

Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, Taniguchi T, Takeda K, Hori S, Ivanov Ⅱ, Umesaki Y, Itoh K, Honda K. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species[J]. Science, 2011, 331(6015): 337-341.

[DOI]

|

| [5] |

Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2004, 4(7): 499-511.

[DOI]

|

| [6] |

Garidou L, Pomié C, Klopp P, Waget A, Charpentier J, Aloulou M, Giry A, Serino M, Stenman L, Lahtinen S, Dray C, Iacovoni JS, Courtney M, Collet X, Amar J, Servant F, Lelouvier B, Valet P, Eberl G, Fazilleau N, Douin-Echinard V, Heymes C, Burcelin R. The gut microbiota regulates intestinal CD4 T cells expressing ROR γ t and controls metabolic disease[J]. Cell Metab, 2015, 22(1): 100-112.

[DOI]

|

| [7] |

Battaglioli EJ, Hale VL, Chen J, Jeraldo P, Ruiz-Mojica C, Schmidt BA, Rekdal VM, Till LM, Huq L, Smits SA, Moor WJ, Jones-Hall Y, Smyrk T, Khanna S, Pardi DS, Grover M, Patel R, Chia N, Nelson H, Sonnenburg JL, Farrugia G, Kashyap PC. Clostridioides difficile uses amino acids associated with gut microbial dysbiosis in a subset of patients with diarrhea[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2018, 10(464): eaam7019.

[DOI]

|

| [8] |

Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, Wu Y, Schauer P, Smith JD, Allayee H, Tang WH, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease[J]. Nature, 2011, 472(7341): 57-63.

[DOI]

|

| [9] |

Zeuthen LH, Fink LN, Frokiaer H. Epithelial cells prime the immune response to an array of gut-derived commensals towards a tolerogenic phenotype through distinct actions of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and transforming growth factor-beta[J]. Immunology, 2008, 123(2): 197-208.

[URI]

|

| [10] |

Rodriguez-Colman MJ, Schewe M, Meerlo M, Stigter E, Gerrits J, Pras-Raves M, Sacchetti A, Hornsveld M, Oost KC, Snippert HJ, Verhoeven-Duif N, Fodde R, Burgering BM. Interplay between metabolic identities in the intestinal crypt supports stem cell function[J]. Nature, 2017, 543(7645): 424-427.

[DOI]

|

| [11] |

Zmora N, Levy M, Pevsner-Fischer M, Elinav E. Inflammasomes and intestinal inflammation[J]. Mucosal Immunol, 2017, 10(4): 865-883.

[DOI]

|

| [12] |

Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Brereton CF, Lavelle EC, Mills KH. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity[J]. Immunity, 2009, 31(2): 331-341.

[DOI]

|

| [13] |

Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, Ruhn KA, Yu X, Koren O, Ley R, Wakeland EK, Hooper LV. The antibacterial lectin RegⅢ gamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine[J]. Science, 2011, 334(6053): 255-258.

[DOI]

|

| [14] |

Guarda G, So A. Regulation of inflammasome activity[J]. Immunology, 2010, 130(3): 329-336.

[DOI]

|

| [15] |

Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes and their roles in health and disease[J]. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 2012, 28: 137-161.

[DOI]

|

| [16] |

Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013, 13(6): 397-411.

[DOI]

|

| [17] |

McCarthy NE, Eberl M. Human gammadelta T-cell control of mucosal immunity and inflammation[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 985.

[DOI]

|

| [18] |

Sutton CE, Mielke LA, Mills KH. IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells and innate lymphoid cells[J]. Eur J Immunol, 2012, 42(9): 2221-2231.

[DOI]

|

| [19] |

Nava P, Koch S, Laukoetter MG, Lee WY, Kolegraff K, Capaldo CT, Beeman N, Addis C, Gerner-Smidt K, Neumaier I, Skerra A, Li L, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. Interferon-gamma regulates intestinal epithelial homeostasis through converging beta-catenin signaling pathways[J]. Immunity, 2010, 32(3): 392-402.

[DOI]

|

| [20] |

Allaire JM, Crowley SM, Law HT, Chang SY, Ko HJ, Vallance BA. The intestinal epithelium: Central coordinator of mucosal immunity[J]. Trends Immunol, 2018, 39(9): 677-696.

[DOI]

|

| [21] |

Ueno A, Ghosh A, Hung D, Li J, Jijon H. Th17 plasticity and its changes associated with inflammatory bowel disease[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(43): 12283-12295.

[DOI]

|

| [22] |

Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells[J]. Nature, 2006, 441(7090): 235-238.

[DOI]

|

| [23] |

Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression[J]. Immunity, 2009, 30(5): 636-645.

[DOI]

|

| [24] |

Bergsbaken T, Bevan MJ. Proinflammatory microenviron-ments within the intestine regulate the differentiation of tissue-resident CD8+ T cells responding to infection[J]. Nat Immunol, 2015, 16(4): 406-414.

[DOI]

|

| [25] |

Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection[J]. Nat Med, 2006, 12(12): 1365-1371.

[DOI]

|

| [26] |

Muñoz M, Eidenschenk C, Ota N, Wong K, Lohmann U, Kühl AA, Wang X, Manzanillo P, Li Y, Rutz S, Zheng Y, Diehl L, Kayagaki N, van Lookeren-Campagne M, Liesenfeld O, Heimesaat M, Ouyang W. Interleukin-22 induces interleukin-18 expression from epithelial cells during intestinal infection[J]. Immunity, 2015, 42(2): 321-331.

[DOI]

|

| [27] |

Nowarski R, Jackson R, Gagliani N, de Zoete MR, Palm NW, Bailis W, Low JS, Harman CC, Graham M, Elinav E, Flavell RA. Epithelial IL-18 equilibrium controls barrier function in colitis[J]. Cell, 2015, 163(6): 1444-1456.

[DOI]

|

| [28] |

Greenfeder SA, Nunes P, Kwee L, Labow M, Chizzonite RA, Ju G. Molecular cloning and characterization of a second subunit of the interleukin 1 receptor complex[J]. J Biol Chem, 1995, 270(23): 13757-13765.

[DOI]

|

| [29] |

Wlodarska M, Thaiss CA, Nowarski R, Henao-Mejia J, Zhang JP, Brown EM, Frankel G, Levy M, Katz MN, Philbrick WM, Elinav E, Finlay BB, Flavell RA. NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host-microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion[J]. Cell, 2014, 156(5): 1045-1059.

[DOI]

|

| [30] |

Wang S, Xia P, Chen Y, Qu Y, Xiong Z, Ye B, Du Y, Tian Y, Yin Z, Xu Z, Fan Z. Regulatory innate lymphoid cells control innate intestinal inflammation[J]. Cell, 2017, 171(1): 201-216.

[DOI]

|

| [31] |

Brown EM, Sadarangani M, Finlay BB. The role of the immune system in governing host-microbe interactions in the intestine[J]. Nat Immunol, 2013, 14(7): 660-667.

[DOI]

|

| [32] |

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death[J]. Nature, 2015, 526(7575): 660-665.

[DOI]

|

| [33] |

Lei-Leston AC, Murphy AG, Maloy KJ. Epithelial cell inflammasomes in intestinal immunity and inflammation[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 1168.

[DOI]

|

| [34] |

Broz P, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2016, 16(7): 407-420.

[DOI]

|

| [35] |

Ben-Sasson SZ, Hu-Li J, Quiel J, Cauchetaux S, Ratner M, Shapira I, Dinarello CA, Paul WE. IL-1 acts directly on CD4 T cells to enhance their antigen-driven expansion and differentiation[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2009, 106(17): 7119-7124.

[DOI]

|

| [36] |

Chou RC, Kim ND, Sadik CD, Seung E, Lan Y, Byrne MH, Haribabu B, Iwakura Y, Luster AD. Lipid-cytokine-chemokine cascade drives neutrophil recruitment in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis[J]. Immunity, 2010, 33(2): 266-278.

[DOI]

|

| [37] |

Afonina IS, Muller C, Martin SJ, Beyaert R. Proteolytic processing of interleukin-1 family cytokines: Variations on a common theme[J]. Immunity, 2015, 42(6): 991-1004.

[DOI]

|

| [38] |

Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, Peaper DR, Bertin J, Eisenbarth SC, Gordon JI, Flavell RA. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis[J]. Cell, 2011, 145(5): 745-757.

[DOI]

|

| [39] |

Knodler LA, Crowley SM, Sham HP, Yang H, Wrande M, Ma C, Ernst RK, Steele-Mortimer O, Celli J, Vallance BA. Noncanonical inflammasome activation of caspase-4/caspase-11 mediates epithelial defenses against enteric bacterial pathogens[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2014, 16(2): 249-256.

[DOI]

|

| [40] |

Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli VG, Wu H, Lieberman J. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores[J]. Nature, 2016, 535(7610): 153-158.

[DOI]

|

| [41] |

Aglietti RA, Dueber EC. Recent insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying pyroptosis and Gasdermin family functions[J]. Trends Immunol, 2017, 38(4): 261-271.

[DOI]

|

| [42] |

Zhu S, Ding S, Wang P, Wei Z, Pan W, Palm NW, Yang Y, Yu H, Li HB, Wang G, Lei X, de Zoete MR, Zhao J, Zheng Y, Chen H, Zhao Y, Jurado KA, Feng N, Shan L, Kluger Y, Lu J, Abraham C, Fikrig E, Greenberg HB, Flavell RA. Nlrp9b inflammasome restricts rotavirus infection in intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Nature, 2017, 546(7660): 667-670.

[DOI]

|

| [43] |

Ruiz PA, Moron B, Becker HM, Lang S, Atrott K, Spalinger MR, Scharl M, Wojtal KA, Fischbeck-Terhalle A, Frey-Wagner I, Hausmann M, Kraemer T, Rogler G. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles exacerbate DSS-induced colitis: role of the NLRP3 inflammasome[J]. Gut, 2017, 66(7): 1216-1224.

[DOI]

|

| [44] |

Villani AC, Lemire M, Fortin G, Louis E, Silverberg MS, Collette C, Baba N, Libioulle C, Belaiche J, Bitton A, Gaudet D, Cohen A, Langelier D, Fortin PR, Wither JE, Sarfati M, Rutgeerts P, Rioux JD, Vermeire S, Hudson TJ, Franchimont D. Common variants in the NLRP3 region contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility[J]. Nat Genet, 2009, 41(1): 71-76.

[DOI]

|

| [45] |

Schoultz I, Verma D, Halfvarsson J, Törkvist L, Fredrikson M, Sjöqvist U, Lördal M, Tysk C, Lerm M, Söderkvist P, Söderholm JD. Combined polymorphisms in genes encoding the inflammasome components NALP3 and CARD8 confer susceptibility to Crohn's disease in Swedish men[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2009, 104(5): 1180-1188.

[DOI]

|

| [46] |

Sokolovska A, Becker CE, Ip WK, Rathinam VA, Brudner M, Paquette N, Tanne A, Vanaja SK, Moore KJ, Fitzgerald KA, Lacy-Hulbert A, Stuart LM. Activation of caspase-1 by the NLRP3 inflammasome regulates the NADPH oxidase NOX2 to control phagosome function[J]. Nat Immunol, 2013, 14(6): 543-553.

[DOI]

|

| [47] |

Janowski AM, Kolb R, Zhang W, Sutterwala FS. Beneficial and detrimental roles of NLRs in carcinogenesis[J]. Front Immunol, 2013, 4: 370.

[DOI]

|

| [48] |

Robblee MM, Kim CC, Porter Abate J, Valdearcos M, Sandlund KL, Shenoy MK, Volmer R, Iwawaki T, Koliwad SK. Saturated fatty acids engage an IRE1alpha-dependent pathway to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in myeloid cells[J]. Cell Rep, 2016, 14(11): 2611-2623.

[DOI]

|

| [49] |

Bitzer ZT, Wopperer AL, Chrisfield BJ, Tao L, Cooper TK, Vanamala J, Elias RJ, Hayes JE, Lambert JD. Soy protein concentrate mitigates markers of colonic inflammation and loss of gut barrier function in vitro and in vivo[J]. J Nutr Biochem, 2017, 40: 201-208.

[DOI]

|

| [50] |

Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, Vucic D, French DM, Lee WP, Roose-Girma M, Erickson S, Dixit VM. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf[J]. Nature, 2004, 430(6996): 213-218.

[DOI]

|

| [51] |

Rauch I, Deets KA, Ji DX, von Moltke J, Tenthorey JL, Lee AY, Philip NH, Ayres JS, Brodsky IE, Gronert K, Vance RE. NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasomes coordinate intestinal epithelial cell expulsion with eicosanoid and IL-18 release via activation of caspase-1 and -8[J]. Immunity, 2017, 46(4): 649-659.

[DOI]

|

| [52] |

Canna SW, de Jesus AA, Gouni S, Brooks SR, Marrero B, Liu Y, DiMattia A, Zaal KJ, Sanchez GA, Kim H, Chapelle D, Plass N, Huang Y, Villarino AV, Biancotto A, Fleisher TA, Duncan JA, O'Shea JJ, Benseler S, Grom A, Deng Z, Laxer RM, Goldbach-Mansky R. An activating NLRC4 inflammasome mutation causes autoinflammation with recurrent macrophage activation syndrome[J]. Nat Genet, 2014, 46(10): 1140-1146.

[DOI]

|

| [53] |

Sadasivam S, Gupta S, Radha V, Batta K, Kundu TK, Swarup G. Caspase-1 activator Ipaf is a p53-inducible gene involved in apoptosis[J]. Oncogene, 2005, 24(4): 627-636.

[DOI]

|

| [54] |

Wlodarska M, Thaiss CA, Nowarski R, Henao-Mejia J, Zhang JP, Brown EM, Frankel G, Levy M, Katz MN, Philbrick WM, Elinav E, Finlay BB, Flavell RA. NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host-microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion[J]. Cell, 2014, 156(5): 1045-1059.

[DOI]

|

| [55] |

Birchenough GM, Nyström EE, Johansson ME, Hansson GC. A sentinel goblet cell guards the colonic crypt by triggering Nlrp6-dependent Muc2 secretion[J]. Science, 2016, 352(6293): 1535-1542.

[DOI]

|

| [56] |

Wang P, Zhu S, Yang L, Cui S, Pan W, Jackson R, Zheng Y, Rongvaux A, Sun Q, Yang G, Gao S, Lin R, You F, Flavell R, Fikrig E. Nlrp6 regulates intestinal antiviral innate immunity[J]. Science, 2015, 350(6262): 826-830.

[DOI]

|

| [57] |

Levy M, Thaiss CA, Zeevi D, Dohnalová L, Zilberman-Schapira G, Mahdi JA, David E, Savidor A, Korem T, Herzig Y, Pevsner-Fischer M, Shapiro H, Christ A, Harmelin A, Halpern Z, Latz E, Flavell RA, Amit I, Segal E, Elinav E. Microbiota-modulated metabolites shape the intestinal microenvironment by regulating NLRP6 inflammasome signaling[J]. Cell, 2015, 163(6): 1428-1443.

[DOI]

|

| [58] |

Sun Y, Zhang M, Chen CC, Gillilland M 3rd, Sun X, El-Zaatari M, Huffnagle GB, Young VB, Zhang J, Hong SC, Chang YM, Gumucio DL, Owyang C, Kao JY. Stress-induced corticotropin-releasing hormone-mediated NLRP6 inflammasome inhibition and transmissible enteritis in mice[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144(7): 1478-1487, 1487.e1-1487.e8.

[DOI]

|

| [59] |

Chen L, Wilson JE, Koenigsknecht MJ, Chou WC, Montgomery SA, Truax AD, Brickey WJ, Packey CD, Maharshak N, Matsushima GK, Plevy SE, Young VB, Sartor RB, Ting JP. NLRP12 attenuates colon inflammation by maintaining colonic microbial diversity and promoting protective commensal bacterial growth[J]. Nat Immunol, 2017, 18(5): 541-551.

[DOI]

|

| [60] |

Bürckstümmer T, Baumann C, Blüml S, Dixit E, Dürnberger G, Jahn H, Planyavsky M, Bilban M, Colinge J, Bennett KL, Superti-Furga G. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome[J]. Nat Immunol, 2009, 10(3): 266-272.

[DOI]

|

| [61] |

Hu B, Jin C, Li HB, Tong J, Ouyang X, Cetinbas NM, Zhu S, Strowig T, Lam FC, Zhao C, Henao-Mejia J, Yilmaz O, Fitzgerald KA, Eisenbarth SC, Elinav E, Flavell RA. The DNA-sensing AIM2 inflammasome controls radiation-induced cell death and tissue injury[J]. Science, 2016, 354(6313): 765-768.

[DOI]

|

| [62] |

Woerner SM, Kloor M, Schwitalle Y, Youmans H, Doeberitz M, Gebert J, Dihlmann S.[J]. Genes Chromesomes Cancer, 2007, 46(12): 1080-1089.

|

| [63] |

Wilson JE, Petrucelli AS, Chen L, Koblansky AA, Truax AD, Oyama Y, Rogers AB, Brickey WJ, Wang Y, Schneider M, Mühlbauer M, Chou WC, Barker BR, Jobin C, Allbritton NL, Ramsden DA, Davis BK, Ting JP. Inflammasome-independent role of AIM2 in suppressing colon tumorigenesis via DNA-PK and Akt[J]. Nat Med, 2015, 21(8): 906-913.

[DOI]

|

| [64] |

Hu S, Peng L, Kwak YT, Tekippe EM, Pasare C, Malter JS, Hooper LV, Zaki MH. The DNA sensor AIM2 maintains intestinal homeostasis via regulation of epithelial antimicrobial host defense[J]. Cell Rep, 2015, 13(9): 1922-1936.

[DOI]

|

| [65] |

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death[J]. Nature, 2015, 526(7575): 660-665.

[DOI]

|

| [66] |

Tamura M, Tanaka S, Fujii T, Aoki A, Komiyama H, Ezawa K, Sumiyama K, Sagai T, Shiroishi T. Members of a novel gene family, Gsdm, are expressed exclusively in the epithelium of the skin and gastrointestinal tract in a highly tissue-specific manner[J]. Genomics, 2007, 89(5): 618-629.

[DOI]

|

| [67] |

Kovacs SB, Miao EA. Gasdermins: Effectors of pyroptosis[J]. Trends Cell Biol, 2017, 27(9): 673-684.

[DOI]

|

| [68] |

Zhu S, Ding S, Wang P, Wei Z, Pan W, Palm NW, Yang Y, Yu H, Li HB, Wang G, Lei X, de Zoete MR, Zhao J, Zheng Y, Chen H, Zhao Y, Jurado KA, Feng N, Shan L, Kluger Y, Lu J, Abraham C, Fikrig E, Greenberg HB, Flavell RA. Nlrp9b inflammasome restricts rotavirus infection in intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Nature, 2017, 546(7660): 667-670.

[DOI]

|

| [69] |

Saeki N, Usui T, Aoyagi K, Kim DH, Sato M, Mabuchi T, Yanagihara K, Ogawa K, Sakamoto H, Yoshida T, Sasaki H. Distinctive expression and function of four GSDM family genes (GSDMA-D) in normal and malignant upper gastrointestinal epithelium[J]. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 2009, 48(3): 261-271.

[URI]

|

2019, Vol. 14

2019, Vol. 14