人乳头瘤病毒(human papillomavirus,HPV)是性病传播感染最常见的病原体之一。HPV有170多种基因型,根据致癌潜力,该病毒被分为高危型和低危型两种。低危型HPV为常引起生殖器疣和喉乳头状瘤的病原体[1]。高危型HPV16和18的感染与95%的宫颈鳞状细胞癌有关[2],也与头颈部肿瘤有密切关系[3-4]。肛门生殖器、口咽部癌与HPV的因果关系已得到很好确立,抗病毒研究已逐步成为国际热点。

1 HPVHPV属乳头瘤病毒科微小乳头瘤病毒,为无包膜的二十面体DNA病毒。病毒颗粒直径为55~60 nm,由共价单链双分子组成封闭的约7 900 bp的环状DNA基因组(图 1)。所有的编码序列位于一条DNA链上,含有至少6个早期开放读码框(open reading frame, ORF)、2个晚期ORF、控制区(LCR)、上游调控区(URR)或非编码区域(NCR)。

|

| ORFs deduced from the DNA sequence are designated E1 to E8, L1, and L2, indicated in grey boxes. A non-coding region (NCR) is indicated by a black box. Main functions of genes are listed. 图 1 HPV16的基因组组成及其主要功能 Fig. 1 Genomic organization of HPV16 |

HPV基因分型基于其主要衣壳蛋白L1 ORF内部的同源性[5-6]。根据1995年魁北克国际乳头状瘤病毒研讨会的商定[7],如新分离株的L1 ORF的DNA序列与最接近的已知类型相差超过10%,定为新型; 如相差介于2%~10%,可称为亚型; 若<2%则为变异株。目前,170多种HPV基因型已全部被测序,各自有其不同的生命周期特征和致癌潜力[8-11]。

1.1.2 黏膜和皮肤型据被HPV感染后先出现病变的位置,分为皮肤型和黏膜型。皮肤疣与皮肤型HPV相关,主要由HPV1、2、4引起;但也可能由HPV5、8、9、23、47引起,被紫外线照射后可转为恶性肿瘤[12-13]。黏膜型HPV存在于呼吸道和生殖器官黏膜表面。目前已有40多种HPV被确定,最常见的为HPV6、11、16、18、33等[5]。

1.1.3 高危和低危型以病毒不同的致癌潜力区分病毒类型。Munoz等认为,高危型有15种,包括HPV16、18、31、33、35、39、45、51、52、56、58、59、68、73和82;此外,HPV26、53、66被分为可能高危型; 低危型包括HPV6、11、40、42、43、44、54、61、70、72、81和CP6108[2]。

1.2 传播途径HPV的传播途径包括水平传播和垂直传播。在水平传播模式中以性传播途径最为常见[14],也有报道在无性生活史的成人和儿童中可通过自、异体接种或污染物传播[15-17]。垂直传播途径指被HPV感染的母亲可能在生产过程中及产后的密切接触中将病毒感染婴儿[18]。Chen等报道约有5%学龄前幼儿及10%学生的扁桃体上皮组织中被检出HPV16 DNA,进一步支持HPV可通过垂直型传播[19]。

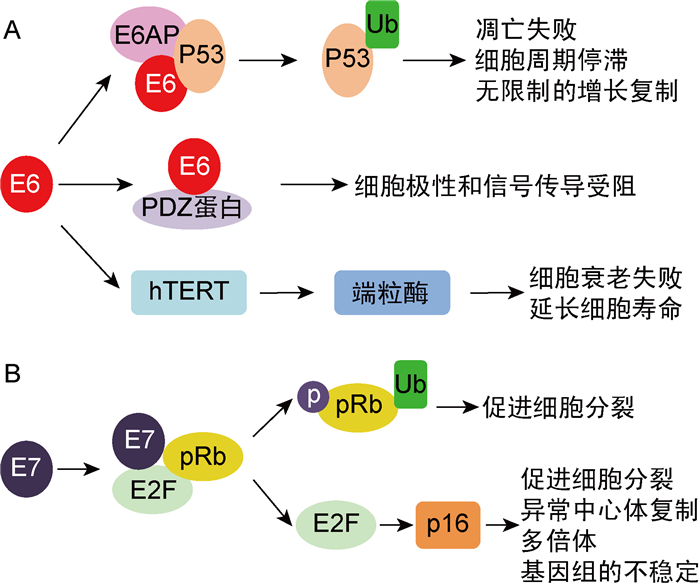

1.3 致癌机制1995年,国际癌症研究机构(International Agency for Research on Cancer,IARC)将HPV16和18定性为人类致癌物,是宫颈癌的主要病因[20-22]。高危型HPV有2个主要的肿瘤蛋白E6和E7。E6蛋白通过与细胞E6相关蛋白(E6AP)及肿瘤抑制蛋白P53相结合,导致P53泛素化蛋白酶体降解及抗细胞凋亡,使细胞周期停滞或无限增殖。E6蛋白也可与细胞PDZ蛋白结合,导致细胞极性和信号传导的破坏。此外,E6蛋白还可以激活细胞端粒酶(hTERT),引起细胞无限增殖[24-25](图 2A)。E7蛋白可使抗视网膜母细胞瘤的肿瘤抑制蛋白pRb磷酸化和泛素化,从而促进细胞分裂。同时,E7蛋白可激活细胞转录因子E2F,通过细胞肿瘤抑制蛋白p16途径,促进细胞分裂,诱导异常中心体复制,使多倍体和基因组不稳定[23-24](图 2B)。

1.4 辅因子高危型HPV感染是癌症发生的必要但非充分条件。永生化细胞为正常原代细胞被HPV16的DNA转染后建立的,该细胞植入裸鼠体内未能致癌,表明由HPV16转化的永生化细胞是非恶性的[26-29]。在被高危型HPV感染的妇女中,长期口服避孕药、吸烟及与其他性传播因素的共同作用是影响其进展为宫颈癌的辅助风险因素[26-29]。

|

| 图 2 高危型HPV E6和E7肿瘤蛋白与细胞蛋白相互作用的致癌机制 Fig. 2 Molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis by high-risk HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins interacting with cellular proteins |

全球约5%的癌症病例由高危型HPV感染引起[30]。在美国,高危型HPV导致女性癌症病例占3%,男性癌症病例占2%[31]。几乎所有的宫颈癌均由HPV导致,其中HPV16和18占70%,其余为45、31、33、52、58、35等[2, 32]。约80%的肛门癌,65%的阴道癌,50%的外阴癌和35%的阴茎癌由HPV引起,以16型最为常见[33-34]。

约70%的口咽癌(包括软腭、舌根和扁桃体)由HPV引起,其中有一半以上与HPV16相关[3-4]。越来越多的报道证实头颈部鳞状细胞癌(head and neck squamous cell carcinoma,HNSCC)中存在HPV,总体检测率为9%~60%[35-37]。原位杂交法显示HPV DNA只存在于肿瘤细胞中,不位于周围基质或非发育不良表面上皮中[38-39]。HPV DNA阳性的HNSCC中,约有50%患者表达E6/E7 mRNA[40-41],伴有高表达p16、野生型P53和低表达pRb;相反,缺乏E6/E7 mRNA表达的肿瘤通常与低表达p16、突变型P53及正常pRb相关[40]。研究证实高危型HPV与HNSCC间存在的因果关系。值得注意的是HPV导致的头颈部肿瘤与肛门生殖器癌症有所不同,在HNSCC中HPV DNA和P53突变共存,E6转录物表达与基底样形态(细胞拥挤、形态小、色度过高、细胞质稀少、细胞核显示活跃的有丝分裂和无角质化特征)相关[42-44]。相反,肛门生殖器癌症的HPV阳性与P53突变之间呈负相关,且通常无明显的基底样形态组织学特征[7]。

扁桃体鳞状细胞癌亦为头颈部肿瘤。使用不同的检测方法,约有42%~100%的扁桃体癌中可检测出HPV DNA[35]。HPV阳性的扁桃体鳞状细胞癌被认为具有独特的生物学特征,如通常见于不吸烟饮酒的中年男性,以HPV16最为常见,伴有癌基因E6/E7表达,p16表达增高,而pRb表达降低,P53低表达野生型[40-41]。HPV阳性扁桃体癌的预后通常比HPV阴性扁桃体癌患者好[35]。流行病学数据显示,与HPV相关的肛门生殖器癌症患者患扁桃体鳞癌风险增加4.3倍,而与HPV非相关癌症(结肠癌、胃癌和乳腺癌)患者不增加发生扁桃体鳞状细胞癌的风险,提示HPV可能是关联扁桃体与肛门生殖器之间发生鳞状细胞癌的常见因素[45]。

3 治疗HPV感染的个体根据发展为肿瘤的类型和阶段,通常接受与非HPV感染的癌症患者相同的治疗。用于治疗宫颈癌前病变的方法通常包括冷冻破坏手术、环形电外科切除术等。宫颈癌的治疗方案根据临床症状而定,一般为手术、化疗、放疗、免疫治疗以及临床试用期的治疗性疫苗。

另外,抗HPV研究逐步成为国际热点。Jiang实验室已证实,经化学修饰的牛乳清蛋白可以高效阻断HPV感染, 对高危型HPV持续性感染的阻断有显著效果,且具有很好的临床安全性[46-48]。此外,干扰素也具有调节免疫力、抗病毒增殖的作用。肛门生殖器疣的消融治疗后,全身施用干扰素可增加病毒清除率并降低复发率,但与文献报道的疗效不一致[49]。

4 预防HPV疫苗的出现是肿瘤预防科研取得的重大成果。疫苗可预防HPV感染,从而预防全球2/3以上的浸润性宫颈癌和一半的高度鳞状上皮内病变[50]。HPV疫苗是由通过重组DNA技术表达的具有与HPV相同的主要外壳蛋白质L1产生的病毒样颗粒(virus-like particle,VLP)组成, 没有HPV的遗传物质。VLP作为抗原可诱导人体产生强烈的保护性免疫应答(抗L1蛋白的抗体),以便在再次接触HPV时,抑制其遗传物质的释放[51]。至今,美国食品和药品管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)已经批准了3种预防HPV感染的疫苗。2006年,4价HPV疫苗获得许可,其包含由HPV 6、11、16和18 L1蛋白制备的4种特异性VLP。2007年2价疫苗开始销售,其包含由16和18的2种病毒L1制备的VLP[52]。2014年12月,美国FDA批准了9价疫苗上市,可保护9种HPV的感染(6、11、16、18、31、33、45、52和58)。疫苗以2个或3个剂量系列给药,世界卫生组织建议让9~13岁的青少年在有性行为之前接种[53],降低由疫苗靶向的HPV感染的风险,但不能治疗由HPV感染所致的疾病[54-55]。HPV疫苗的接种被引入可作为预防宫颈癌的措施,但不能替代宫颈癌的筛查[56]。尽管信息有限,但已报道HPV疫苗在预防病毒感染方面具有免疫原性、安全性和有效性,目前尚无严重的不良反应[57-58]。各国政府在大量科研证据的基础上,应推广HPV疫苗接种以达到有效的预防目的。同时需要更多研究开发针对HPV相关癌症的治疗性疫苗,以提高治疗HPV相关癌症的效果。

5 结语HPV是一种常见的性传播疾病病原体,可导致肛门、生殖器和头颈部癌症。通过对该病毒结构生物学的研究,人们已部分掌握了HPV的重要细节,研发出用于预防和控制HPV相关癌症的高免疫原性和有效的疫苗。组合疗法的优化和计算机辅助设计将进一步提供研发和治疗方案。

| [1] |

Blake DR, Middleman AB. Human papillomavirus vaccine update[J]. Pediatr Clin North Am, 2017, 64(2): 321-329.

[DOI]

|

| [2] |

Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2003, 348(6): 518-527.

[DOI]

|

| [3] |

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, Jiang B, Goodman MT, Sibug-Saber M, Cozen W, Liu L, Lynch CF, Wentzensen N, Jordan RC, Altekruse S, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(32): 4294-4301.

[DOI]

|

| [4] |

Koskinen WJ, Chen RW, Leivo I, Mäkitie A, Bäck L, Kontio R, Suuronen R, Lindqvist C, Auvinen E, Molijn A, Quint WG, Vaheri A, Aaltonen LM. Prevalence and physical status of human papillomavirus in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck[J]. Int J Cancer, 2003, 107(3): 401-406.

[DOI]

|

| [5] |

de Villiers EM. Papillomavirus and HPV typing[J]. Clin Dermatol, 1997, 15(2): 199-206.

[URI]

|

| [6] |

de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses[J]. Virology, 2004, 324: 17-27.

[DOI]

|

| [7] |

zur Hausen H. Papillomavirus infections — a major cause of human cancers[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1996, 1288(2): F55-F78.

[DOI]

|

| [8] |

de Villiers EM. Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses[J]. Virology, 2013, 445(1-2): 2-10.

[DOI]

|

| [9] |

Tsakogiannis D, Gartzonika C, Levidiotou-Stefanou S, Markoulatos P. Molecular approaches for HPV genotyping and HPV-DNA physical status[J]. Expert Rev Mol Med, 2017, 19: e1.

[DOI]

|

| [10] |

Chen Z, de Freitas LB, Burk RD. Evolution and classification of oncogenic human papillomavirus types and variants associated with cervical cancer[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2015, 1249: 3-26.

[DOI]

|

| [11] |

Tommasino M. The human papillomavirus family and its role in carcinogenesis[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2014, 26: 13-21.

[DOI]

|

| [12] |

Androphy EJ. Molecular biology of human papillomavirus infection and oncogenesis[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 1994, 103(2): 248-256.

[DOI]

|

| [13] |

Pfister H. Chapter 8: Human papillomavirus and skin cancer[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 2003(31): 52-56.

[DOI]

|

| [14] |

Burchell AN, Winer RL, de Sanjosé S, Franco EL. Chapter 6: Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of genital HPV infection[J]. Vaccine, 2006, 24(Suppl 3): S52-S61.

[DOI]

|

| [15] |

Pao CC, Tsai PL, Chang YL, Hsieh TT, Jin JY. Possible non-sexual transmission of genital human papillomavirus infections in young women[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 1993, 12(3): 221-222.

[DOI]

|

| [16] |

Doerfler D, Bernhaus A, Kottmel A, Sam C, Koelle D, Joura EA. Human papilloma virus infection prior to coitarche[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2009, 200(5): 487.e1-487.e5.

[DOI]

|

| [17] |

M'Zali F, Bounizra C, Leroy S, Mekki Y, Quentin-Noury C, Kann M. Persistence of microbial contamination on transvaginal ultrasound probes despite low-level disinfection procedure[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(4): e93368.

[DOI]

|

| [18] |

Castellsagué X, Drudis T, Cañadas MP, Goncé A, Ros R, Pérez JM, Quintana MJ, Muñoz J, Albero G, de Sanjosé S, Bosch FX. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in pregnant women and mother-to-child transmission of genital HPV genotypes: a prospective study in Spain[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2009, 9: 74.

[DOI]

|

| [19] |

Chen R, Sehr P, Waterboer T, Leivo I, Pawlita M, Vaheri A, Aaltonen LM. Presence of DNA of human papillomavirus 16 but no other types in tumor-free tonsillar tissue[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2005, 43(3): 1408-1410.

[DOI]

|

| [20] |

zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in human cancers[J]. Proc Assoc Am Physicians, 1999, 111(6): 581-587.

[DOI]

|

| [21] |

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Ingested nitrate and nitrite, and cyanobacterial peptide toxins [M/OL]. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum, 2010, 94: v-vii, 1-412.

|

| [22] |

zur Hausen H. Human papillomaviruses in the pathogenesis of anogenital cancer[J]. Virology, 1991, 184(1): 9-13.

[DOI]

|

| [23] |

Münger K, Basile JR, Duensing S, Eichten A, Gonzalez SL, Grace M, Zacny VL. Biological activities and molecular targets of the human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein[J]. Oncogene, 2001, 20(54): 7888-7898.

[DOI]

|

| [24] |

Scheffner M, Whitaker NJ. Human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis and the ubiquitin-proteasome system[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2003, 13(1): 59-67.

[DOI]

|

| [25] |

Mantovani F, Banks L. The human papillomavirus E6 protein and its contribution to malignant progression[J]. Oncogene, 2001, 20(54): 7874-7887.

[DOI]

|

| [26] |

Castellsagué X, Bosch FX, Muñoz N. Environmental co-factors in HPV carcinogenesis[J]. Virus Res, 2002, 89(2): 191-199.

[DOI]

|

| [27] |

Shi R, Devarakonda S, Liu L, Taylor H, Mills G. Factors associated with genital human papillomavirus infection among adult females in the United States, NHANES 2007-2010[J]. BMC Res Notes, 2014, 7: 544.

[DOI]

|

| [28] |

Zheng J, Saksela O, Matikainen S, Vaheri A. Keratinocyte growth factor is a bifunctional regulator of HPV16 DNA-immortalized cervical epithelial cells[J]. J Cell Biol, 1995, 129(3): 843-851.

[DOI]

|

| [29] |

Chen RW, Aalto Y, Teesalu T, Dürst M, Knuutila S, Aaltonen LM, Vaheri A. Establishment and characterisation of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA immortalised human tonsillar epithelial cell lines[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2003, 39(5): 698-707.

[DOI]

|

| [30] |

de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infectins in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2012, 13(6): 607-615.

[DOI]

|

| [31] |

Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, Eheman C, Saraiya M, Bandi P, Saslow D, Cronin KA, Watson M, Schiffman M, Henley SJ, Schymura MJ, Anderson RN, Yankey D, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2013, 105(3): 175-201.

[DOI]

|

| [32] |

Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, O'Reilly S, Kiviat NB, Holmes KK, Koutsky LA. Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 354(25): 2645-2654.

[DOI]

|

| [33] |

Lin C, Franceschi S, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus types from infection to cancer in the anus, according to sex and HIV status: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2018, 18(2): 198-206.

[DOI]

|

| [34] |

Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Lowy DR. HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women[J]. Cancer, 2008, 113(Suppl 10): 3036-3046.

[DOI]

|

| [35] |

Chen R, Aaltonen LM, Vaheri A. Human papillomavirus type 16 in head and neck carcinogenesis[J]. Rev Med Virol, 2005, 15(6): 351-363.

[DOI]

|

| [36] |

Mork J, Lie AK, Glattre E, Hallmans G, Jellum E, Koskela P, Møller B, Pukkala E, Schiller JT, Youngman L, Lehtinen M, Dillner J. Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck[J]. N Engl J Med, 2001, 344(15): 1125-1131.

[DOI]

|

| [37] |

Miller CS, Johnstone BM. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis, 1982-1997[J]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 2001, 91(6): 622-635.

[DOI]

|

| [38] |

Niedobitek G, Pitteroff S, Herbst H, Shepherd P, Finn T, Anagnostopoulos I, Stein H. Detection of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA in carcinomas of the palatine tonsil[J]. J Clin Pathol, 1990, 43(11): 918-921.

[DOI]

|

| [39] |

Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2000, 92(9): 709-720.

[DOI]

|

| [40] |

Wiest T, Schwarz E, Enders C, Flechtenmacher C, Bosch FX. Involvement of intact HPV16 E6/E7 gene expression in head and neck cancers with unaltered p53 status and perturbed pRB cell cycle control[J]. Oncogene, 2002, 21(10): 1510-1517.

[DOI]

|

| [41] |

Balz V, Scheckenbach K, Götte K, Bockmühl U, Petersen I, Bier H. Is the p53 inactivation frequency in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck underestimated? Analysis of p53 exons 2-11 and human papillomavirus 16/18 E6 transcripts in 123 unselected tumor specimens[J]. Cancer Res, 2003, 63(6): 1188-1191.

[DOI]

|

| [42] |

van Houten VM, Snijders PJ, van den Brekel MW, Kummer JA, Meijer CJ, van Leeuwen B, Denkers F, Smeele LE, Snow GB, Brakenhoff RH. Biological evidence that human papillomaviruses are etiologically involved in a subgroup of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas[J]. Int J Cancer, 2001, 93(2): 232-235.

[DOI]

|

| [43] |

Chiba I, Shindoh M, Yasuda M, Yamazaki Y, Amemiya A, Sato Y, Fujinaga K, Notani K, Fukuda H. Mutations in the p53 gene and human papillomavirus infection as significant prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity[J]. Oncogene, 1996, 12(8): 1663-1668.

[DOI]

|

| [44] |

Scholes AG, Liloglou T, Snijders PJ, Hart CA, Jones AS, Woolgar JA, Vaughan ED, Walboomers JM, Field JK. p53 mutations in relation to human papillomavirus type 16 infection in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck[J]. Int J Cancer, 1997, 71(5): 796-799.

[DOI]

|

| [45] |

Frisch M, Biggar RJ. Aetiological parallel between tonsillar and anogenital squamous-cell carcinomas[J]. Lancet, 1999, 354(9188): 1442-1443.

[DOI]

|

| [46] |

Lu L, Yang X, Li Y, Jiang S. Chemically modified bovine beta-lactoglobulin inhibits human papillomavirus infection[J]. Microbes Infect, 2013, 15(6-7): 506-510.

[DOI]

|

| [47] |

Guo X, Qiu L, Wang Y, Wang Y, Wang Q, Song L, Li Y, Huang K, Du X, Fan W, Jiang S, Wang Q, Li H, Yang Y, Meng Y, Zhu Y, Lu L, Jiang S. A randomized open-label clinical trial of an anti-HPV biological dressing (JB01-BD) administered intravaginally to treat high-risk HPV infection[J]. Microbes Infect, 2016, 18(2): 148-152.

[DOI]

|

| [48] |

Guo X, Qiu L, Wang Y, Wang Y, Meng Y, Zhu Y, Lu L, Jiang S. Safety evaluation of chemically modified beta‐lactoglobulin administered intravaginally[J]. J Med Virol, 2016, 88(6): 1098-1101.

[DOI]

|

| [49] |

Westfechtel L, Werner RN, Dressler C, Gaskins M, Nast A. Adjuvant treatment of anogenital warts with systemic interferon: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Sex Transm Infect, 2018, 94(1): 21-29.

[DOI]

|

| [50] |

Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, Keys J, Franceschi S, Winer R, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update[J]. Int J Cancer, 2007, 121(3): 621-632.

[DOI]

|

| [51] |

Huang CM. Human papillomavirus and vaccination[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2008, 83(6): 701-707.

[DOI]

|

| [52] |

Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Chesson HW, Curtis CR, Gee J, Bocchini JA Jr, Unger ER, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)[J]. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2014, 63(RR-05): 1-30.

|

| [53] |

World Health Organization. Chapter 4. HPV vaccination [M]. In: Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, 2014: 107-128.

|

| [54] |

Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Rodriguez AC, Solomon D, Bratti MC, Schiller JT, Gonzalez P, Dubin G, Porras C, Jimenez SE, Lowy DR, Costa Rican HPV Vaccine Trial Group. Effect of human papillomavirus 16/18 L1 viruslike particle vaccine among young women with preexisting infection: a randomized trial[J]. JAMA, 2007, 298(7): 743-753.

[DOI]

|

| [55] |

Schiller JT, Castellsagué X, Garland SM. A review of clinical trials of human papillomavirus prophylactic vaccines[J]. Vaccine, 2012, 30(Suppl 5): F123-F138.

[DOI]

|

| [56] |

Giorgi Rossi P, Carozzi F, Federici A, Ronco G, Zappa M, Franceschi S, Italian Screening in HPV Vaccinated Girls Consensus Conference Group. Cervical cancer screening in women vaccinated against human papillomavirus infection: Recommendations from a consensus conference[J]. Prev Med, 2017, 98: 21-30.

[DOI]

|

| [57] |

Phillips A, Patel C, Pillsbury A, Brotherton J, Macartney K. Safety of human papillomavirus vaccines: an updated review[J]. Drug Saf, 2018, 41(4): 329-346.

[DOI]

|

| [58] |

Sabeena S, Bhat PV, Kamath V, Arunkumar G. Global human papilloma virus vaccine implementation: An update[J]. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2018, 44(6): 989-997.

[DOI]

|

2019, Vol. 14

2019, Vol. 14